CPU fetch–decode execute cycle, caches and memory hierarchy, virtual memory, the OS’s role, and how systems communicate over networks.

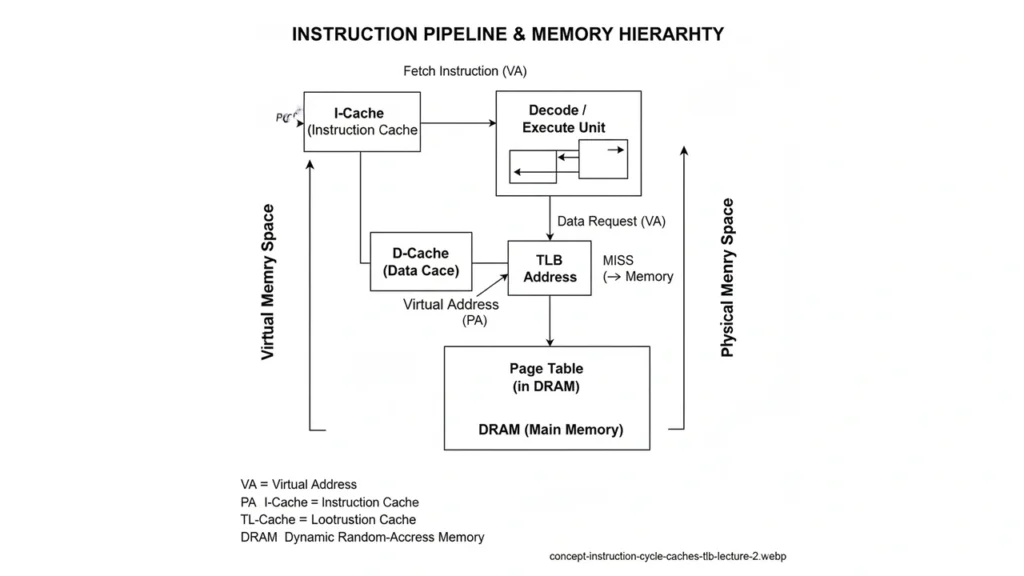

Instruction Execution: Fetch → Decode → Execute

- Fetch: The Program Counter (PC) holds the address of the next instruction. The CPU requests that instruction from L1 I-cache/memory.

- Decode: The control unit translates the instruction into internal control signals (or micro-ops).

- Execute: The ALU, load/store unit, or branch unit performs the operation, possibly reading/writing registers or memory.

- Write-back & PC update: Results go to registers/memory; the PC advances or is changed by a branch/jump.

Modern CPUs overlap these stages with pipelining and may issue multiple instructions per cycle (superscalar, out-of-order).

Why Caches Matter ?

DRAM is far slower than the CPU. Caches keep recently or nearby data close to the core.

- Locality

- Temporal: recently used data likely used again.

- Spatial: nearby addresses likely accessed next.

- Cache anatomy

- Line (block): e.g., 64 bytes fetched on a miss.

- Mapping: direct-mapped, N-way set-associative, or fully associative.

- Replacement: LRU/PLRU/random.

- Write policy: write-back vs write-through; write-allocate vs no-write-allocate.

- Miss types: compulsory (cold), capacity, conflict.

Example: a loop that scans an array linearly benefits from spatial locality; a stride of 64B matches typical line size, while large strides cause more misses.

The Memory & Storage Hierarchy (conceptual latencies)

Registers (≈1 cycle) → L1 (≈4 cycles) → L2 (≈12 cycles) → L3 (≈30–50 cycles) → DRAM (≈100–200 ns) → NVMe SSD (≈100 µs) → HDD (ms) → Network/Cloud (ms–100s ms).

Hierarchy trades speed vs capacity vs cost; software and the OS try to keep working sets near the top.

Lecture 1: Introduction to Computer Systems & Compilation System (Bits, Bytes, and Integers)

Virtual Memory in One Page

- Pages/Frames: virtual address space is split into pages (e.g., 4 KiB), mapped to physical frames.

- Page Table: per-process mapping maintained by the OS; enables isolation and shared pages (e.g., shared libraries).

- TLB: a small cache of recent page translations. A TLB miss forces a page-table walk.

- Page Faults: on missing pages, the OS loads data from disk (slow); on protection faults, the OS may kill the process.

OS Responsibilities You Touch in Assembly

- Process & Thread Scheduling (time slices, priorities).

- System Calls (trap/

int/syscallinstructions): file I/O, memory management (mmap,brk), networking, timers. - Interrupts & Exceptions: device signals and error conditions; the OS dispatches handlers.

- DMA: devices transfer data to memory with minimal CPU intervention.

- Filesystems: logical file view over blocks on storage.

Devices, I/O & Networks

- Device controller ↔ driver: registers (often memory-mapped I/O), queues, interrupts.

- Networking path: user process → socket API → kernel networking stack (TCP/IP) → NIC → wire → remote host.

- Latency vs throughput: small messages pay handshake/RTT costs; large transfers saturate bandwidth.

Mini-Lab

# 1) Observe CPU + caches

lscpu | egrep 'Model name|cache'

# Linux: cat /proc/cpuinfo | less (for more detail)

# 2) Measure memory locality (Python quick test)

python3 - << 'PY'

import numpy as np, time

N=64*1024*1024//8; a=np.zeros(N,dtype=np.int64)

for s in [1,8,64,512,4096]:

t=time.time()

x=0

for i in range(0,N,s): x+=a[i]

print(f"stride={s:4d} time={time.time()-t:.3f}s")

PY

# 3) Basic network path

ping -c 3 8.8.8.8

traceroute google.com # Windows: tracert google.comQuick Check (with answers)

- What architectural principle makes caches effective? Temporal and spatial locality.

- What does the TLB cache? Virtual→physical address translations.

- Which policy delays writes to DRAM until eviction? Write-back.

- What causes a page fault? Access to a virtual page not currently in physical memory.

- Where do system calls execute? In kernel mode via a trap/syscall mechanism.

The approach followed at E Lectures reflects both academic depth and easy-to-understand explanations.

People also ask:

Common policies include LRU, pseudo-LRU, or random; the choice balances hardware cost and hit rate.

A cache miss fetches from the next lower level (often DRAM) and is fast relative to disk; a page fault requires OS intervention and may load from storage, which is much slower.

Not typically; it affects byte ordering in memory and data interchange. We’ll cover details in the ISA/endian lecture.

Linear scans exploit spatial locality, keeping misses low; scattered access defeats the cache’s prefetching and mapping.

Direct Memory Access lets devices move data to RAM without tying up the CPU, improving throughput and reducing latency.