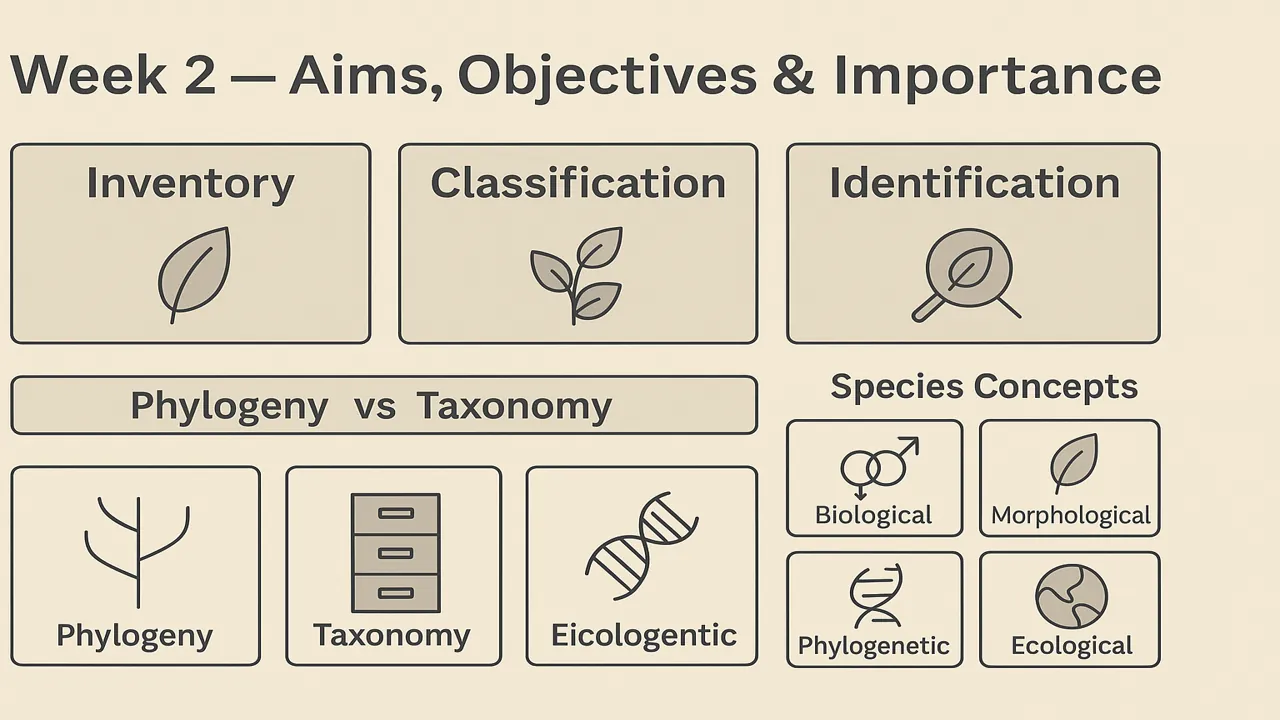

the aims of plant systematics inventory, classification, identification plus phylogeny vs taxonomy, species concepts, and a hands-on character-matrix lab.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this week, students will be able to:

- State and explain the central aims of plant systematics: inventory, classification, identification.

- Differentiate phylogeny (evolutionary relationships) from taxonomy (description, naming, arranging).

- Compare major species concepts (biological, morphological/typological, phylogenetic, ecological) with strengths/limits and example use-cases.

- Build a basic character matrix and compute a simple similarity index to support classification decisions.

- Critically evaluate phenetics, cladistics, and evolutionary/systematic approaches in a 1-page note.

Why Plant Systematics Needs Clear Aims

Plant systematics underpins everything from red-list assessments to crop improvement. To stay rigorous and useful, it pursues three complementary aims:

Inventory (Document Diversity)

- What: Compile floras, monographs, checklists, DNA barcodes; map distributions and endemism.

- Why it matters: Baselines for conservation, biosecurity, restoration planning, and future research.

- Key outputs: Verified species lists, occurrence records, type information.

Classification (Organize Knowledge)

- What: Arrange taxa into a hierarchy (family → genus → species) that reflects relationships.

- Modern goal: Classifications should be phylogeny-informed (monophyletic groups).

- Payoff: Predictive power—knowing a family often predicts traits, chemistry, and ecology.

Identification (Name the Unknown)

- What: Use keys, field guides, DNA barcodes, images, and expert systems to place specimens.

- Why: Correct names connect specimens to legal, medical, agronomic knowledge.

- Deliverables: Illustrated keys, dichotomous/multi-access keys, digital tools.

Phylogeny vs Taxonomy (don’t confuse the goals)

- Phylogeny reconstructs evolutionary history trees built from characters (morphology, molecules, anatomy, palynology).

- Taxonomy describes, names, and arranges taxa, ideally using the best phylogenetic evidence.

- Bottom line: Phylogeny is the hypothesis of relatedness; taxonomy turns that hypothesis into names and ranks that people can use.

Week 1 – Introduction to Plant Systematics: Definitions, Scope, Characters & Real-World Value

What Is a Species? (concepts you should know)

| Concept | Core idea | Strengths | Limitations | Example use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological | Interbreeding, reproductive isolation | Evolutionary focus; powerful for animals | Hybridization, asexuals, fossils complicate it | Crop wild relatives with crossing data |

| Morphological/Typological | Diagnostic form/structure | Field-friendly; works with fossils & herbarium | Cryptic species overlooked; plasticity misleads | Rapid floras, preliminary IDs |

| Phylogenetic | Smallest diagnosable monophyletic unit | DNA friendly; detects cryptic diversity | Over-splitting if criteria strict | Barcoding, tree-based delimitation |

| Ecological | Niche/role defines species | Links to environment and function | Hard to test; overlapping niches | Edaphic/endemic specialists |

In practice, integrative taxonomy synthesizes multiple lines of evidence to delimit species.

The approach followed at E Lectures reflects both academic depth and easy-to-understand explanations.

People also ask:

No. Morphology/anatomy/palynology remain powerful, especially when combined. DNA is transformative but not mandatory for many applied tasks.

For presence/absence data, Jaccard is common; if you treat 0 and 1 symmetrically, SMC is fine. Report which you used.

You can describe and name taxa, but phylogeny strengthens classifications and helps avoid artificial (non-monophyletic) groups.

None universally. Choose the concept that matches your data and purpose; use integrative evidence whenever possible.

Build a small, well-scored character matrix for your local flora and practice with a dichotomous key; you’ll see patterns fast.