This Natural Language Processing question bank is designed for BS Computing students following the NCEAC syllabus. Here you will find 100 MCQs, 30 short questions and 15 long / theory questions covering all topics from Lectures 1–15, including text preprocessing, language modelling, POS tagging, parsing, information extraction, machine translation, question answering and text summarization. Use these questions with the detailed lecture notes on ElecturesAI and the Deep Learning series to prepare for quizzes, midterm and final exams.

A. 100 MCQs with Answers

Q1. Natural Language Processing mainly studies the interaction between

A. Computers and binary data

B. Computers and human languages

C. Humans and operating systems

D. Networks and protocols

Answer. B

Q2. Which of the following is NOT typically considered an NLP task

A. Machine translation

B. Part-of-speech tagging

C. Image classification

D. Named entity recognition

Answer. C

Q3. In a typical high-level NLP pipeline, which step comes first

A. Parsing

B. Text preprocessing and tokenization

C. Language modelling

D. Machine translation

Answer. B

Q4. The main motivation for NLP is to

A. Replace all human translators

B. Allow computers to process and understand human language at scale

C. Eliminate the need for programming languages

D. Store audio more efficiently

Answer. B

Q5. Which subfield is most closely related to NLP

A. Computer graphics

B. Computational linguistics

C. Computer architecture

D. Embedded systems

Answer. B

Q6. Early NLP systems were mostly

A. Data-driven neural models

B. Rule-based systems written by linguists

C. Image-based systems

D. Hardware accelerators

Answer. B

Q7. Which of the following is an example of spoken language processing in NLP

A. Sentence segmentation in text

B. Speech recognition and speech-to-text

C. Byte-code optimization

D. File system indexing

Answer. B

Lecture 1 – Introduction to Natural Language Processing, History, Core Applications

Q8. Converting all tokens to lowercase is an example of

A. Stemming

B. Normalization

C. Parsing

D. Tagging

Answer. B

Q9. Stopword removal is mainly used to

A. Remove rare informative words

B. Remove very frequent function words such as “the” and “is”

C. Remove punctuation only

D. Remove all verbs from text

Answer. B

Q10. A corpus in NLP is best described as

A. A single sentence

B. A hardware device

C. A large, structured collection of texts

D. A probability distribution

Answer. C

Q11. Lemmatization differs from stemming because lemmatization

A. Always produces longer words

B. Maps words to root forms using vocabulary and morphology

C. Works only for nouns

D. Works only for verbs

Answer. B

Q12. Which of the following is typically TRUE for standard corpora

A. They are unlabeled only

B. They may include annotation such as POS tags or parse trees

C. They never require licensing

D. They are always synthetic

Answer. B

Q13. Tokenization is the process of

A. Assigning POS tags

B. Splitting text into units such as words or subwords

C. Translating text into another language

D. Compressing text

Answer. B

Q14. Why are standard corpora important for NLP research

A. They slow down experiments

B. They allow reproducible evaluation and fair comparison

C. They remove the need for algorithms

D. They replace all annotation

Answer. B

Lecture 2 – Text Preprocessing and Standard Corpora in Natural Language Processing

Q15. Minimum edit distance between two strings is defined as

A. Maximum number of matching characters

B. Minimum number of insertions, deletions and substitutions to transform one into the other

C. Number of different characters divided by length

D. Length of the longer string

Answer. B

Q16. In Levenshtein distance, which operations are allowed

A. Insertion only

B. Deletion only

C. Insertion, deletion and substitution

D. Swapping only

Answer. C

Q17. In spelling correction, candidate corrections for an input word are often chosen as words that

A. Have maximal edit distance

B. Have small edit distance in a lexicon

C. Are shorter than the input

D. Occur only once in corpus

Answer. B

Q18. Noisy channel spelling correction typically chooses the correction that

A. Minimizes P(correction | observed)

B. Maximizes P(observed | correction) only

C. Maximizes P(correction) P(observed | correction)

D. Maximizes edit distance

Answer. C

Q19. The dynamic programming table for minimum edit distance has size

A. 1 × 1

B. m × n where m, n are string lengths

C. m + n

D. 2(m + n)

Answer. B

Q20. Which of these is a typical cost setting in basic Levenshtein distance

A. All operations cost 0

B. Insertion=1, deletion=1, substitution=1

C. Insertion=2, deletion=2, substitution=0

D. Only substitutions allowed with cost 2

Answer. B

Q21. Spelling correction models often combine edit distance with

A. Random number generators

B. Language models over words

C. Image filters

D. Hardware acceleration

Answer. B

Lecture 3 – Minimum Edit Distance and Spelling Correction in Natural Language Processing

Q22. A language model estimates

A. P(image | label)

B. P(sentence) or P(word sequence)

C. P(class | features) only

D. Edit distances

Answer. B

Q23. In a bigram language model, probability of a sentence is approximated as

A. Product of unigram probabilities

B. Product of P(wᵢ | wᵢ₋₁)

C. Sum of joint probabilities

D. Product of P(wᵢ | entire history)

Answer. B

Q24. The main purpose of smoothing in n-gram models is to

A. Increase sentence length

B. Shift probability mass to unseen n-grams

C. Remove stopwords

D. Reduce vocabulary size

Answer. B

Q25. Which of the following is a simple smoothing method

A. Gradient descent

B. Add-one (Laplace) smoothing

C. Beam search

D. POS tagging

Answer. B

Q26. Backoff models

A. Ignore lower order n-grams

B. Use lower order n-grams when higher order counts are unreliable or zero

C. Use only unigrams

D. Require no training data

Answer. B

Q27. Perplexity of a language model is

A. Inverse of accuracy

B. Exponential of average negative log probability

C. Number of out of vocabulary words

D. Ratio of bigrams to unigrams

Answer. B

Q28. For a fixed test set, a better language model generally has

A. Higher perplexity

B. Lower perplexity

C. Perplexity always equal to 1

D. Perplexity equal to vocabulary size

Answer. B

Lecture 4 – Language Modeling in Natural Language Processing

Q29. In an HMM for POS tagging, hidden states correspond to

A. Characters

B. Tags such as Noun, Verb, Adjective

C. Documents

D. Languages

Answer. B

Q30. The emission probability in an HMM POS tagger is

A. P(tag | previous tag)

B. P(word | tag)

C. P(tag | word) directly

D. P(document | tag sequence)

Answer. B

Q31. The transition probability in a first-order HMM is typically

A. P(tagᵢ | tagᵢ₋₁)

B. P(wordᵢ | wordᵢ₋₁)

C. P(tagᵢ | wordᵢ)

D. P(wordᵢ | tagᵢ₊₁)

Answer. A

Q32. The Viterbi algorithm is used to

A. Train HMM parameters from scratch

B. Find the most likely sequence of hidden states

C. Compute edit distance

D. Generate random sentences

Answer. B

Q33. A tagset in POS tagging is

A. A list of all words in corpus

B. A set of all possible part-of-speech categories

C. A set of training sentences only

D. A set of bigrams

Answer. B

Q34. Which of the following is a typical challenge in POS tagging

A. Ambiguous words that can have multiple tags

B. Lack of corpora in any language

C. Only numeric data

D. Fixed sentence length

Answer. A

Q35. Accuracy of POS taggers on standard English corpora is usually around

A. 10–20 percent

B. 40–50 percent

C. 90–97 percent

D. 100 percent

Answer. C

Lecture 5 – Hidden Markov Models and POS Tagging in Natural Language Processing

Q36. A context-free grammar consists of terminals, nonterminals, start symbol and

A. Probability tables only

B. Production rules

C. Training labels

D. Hidden states

Answer. B

Q37. Which of the following is generated by a CFG

A. Finite state automata only

B. Parse trees for sentences

C. Weight matrices

D. Confusion matrices

Answer. B

Q38. In deterministic grammars, rules are typically

A. Associated with probabilities

B. Used with fixed choices and no uncertainty

C. Learned only from data

D. Defined only for bigrams

Answer. B

Q39. A probabilistic context-free grammar (PCFG) assigns

A. Costs to terminals only

B. Probabilities to each production rule

C. Probabilities to sentence positions only

D. Perplexity to the entire corpus

Answer. B

Q40. Which parsing algorithm uses dynamic programming over spans of the sentence

A. Greedy left-to-right

B. CYK (CKY) algorithm

C. Gradient descent

D. Beam search in HMMs

Answer. B

Q41. The main purpose of parsing in NLP is to

A. Count characters

B. Identify syntactic structure of sentences

C. Remove stopwords

D. Compress text

Answer. B

Q42. Constituency grammar analyses sentences in terms of

A. Dependency arcs only

B. Phrase constituents such as NP and VP

C. Character n-grams

D. POS tags alone

Answer. B

Lecture 6 – Deterministic and Stochastic Grammars, CFGs and Parsing in NLP

Q43. Semantic role labelling aims to identify

A. Document topics

B. Who did what to whom, when and where

C. Sentence length

D. Morphological roots

Answer. B

Q44. In a simple sentence “The student submitted the assignment yesterday”, the Agent role is

A. The student

B. Submitted

C. The assignment

D. Yesterday

Answer. A

Q45. The Patient or Theme in that sentence is

A. The student

B. Submitted

C. The assignment

D. Yesterday

Answer. C

Q46. Vector space meaning representations (embeddings) map words or sentences to

A. Trees

B. Real-valued vectors in a high-dimensional space

C. Images

D. Hardware registers

Answer. B

Q47. Distributional semantics is often summarized as

A. Words are independent

B. You shall not use context

C. You shall know a word by the company it keeps

D. Words must be sorted alphabetically

Answer. C

Q48. Frame semantics focuses on

A. Single isolated words only

B. Background knowledge structures evoked by words and events

C. Phonetic transcription

D. Compression of texts

Answer. B

Q49. A major challenge in meaning representation is

A. Handling only numeric tokens

B. Ambiguity and context dependence of natural language

C. Lack of corpora

D. No available embeddings

Answer. B

Lecture 7 – Representing Meaning and Semantic Roles in Natural Language Processing

Q50. Sentiment analysis typically classifies text into categories such as

A. Past, present, future

B. Positive, negative, neutral

C. Long, medium, short

D. Formal, informal

Answer. B

Q51. A common application of sentiment analysis is

A. Machine translation

B. Analyzing product reviews and social media opinions

C. POS tagging

D. Tokenization

Answer. B

Q52. A lexicon-based sentiment system mainly uses

A. Manually or automatically built lists of positive and negative words

B. Only deep neural networks

C. Only grammar rules

D. Only random scores

Answer. A

Q53. One challenge for sentiment analysis is

A. Lack of numeric data

B. Sarcasm and irony in user text

C. Fixed sentence structure

D. Small vocabulary size

Answer. B

Q54. In a supervised sentiment classifier, the input features may include

A. Bag of words and n-grams

B. Only audio signals

C. IP addresses

D. File sizes

Answer. A

Q55. When evaluating sentiment analysis, which metric is commonly used

A. BLEU

B. Perplexity

C. Accuracy or F1-score

D. Word error rate

Answer. C

Q56. A major difference between sentiment analysis and generic topic classification is that sentiment

A. Ignores opinion words

B. Focuses on polarity and attitude rather than subject domain

C. Uses no labels

D. Is unsupervised only

Answer. B

Lecture 8 – Sentiment Analysis in Natural Language Processing

Q57. Text classification aims to

A. Generate new text

B. Assign predefined labels such as spam or not spam to documents

C. Compute edit distance

D. Parse sentences

Answer. B

Q58. In the bag-of-words model, documents are represented by

A. Word order sequences

B. Frequency vectors ignoring order

C. Parse trees only

D. Images

Answer. B

Q59. The TF in TF-IDF stands for

A. Term frequency

B. Text function

C. Token form

D. Target feature

Answer. A

Q60. The IDF in TF-IDF downweights

A. Very rare terms

B. Very frequent terms across documents

C. Stopwords only

D. All nouns

Answer. B

Q61. Which classifier is commonly used for baseline text classification

A. Naive Bayes

B. K-means

C. DBSCAN

D. PCA

Answer. A

Q62. Logistic regression for text classification models

A. P(features)

B. P(class | features)

C. P(features | class) only

D. P(word | previous word)

Answer. B

Q63. A common way to evaluate text classification performance is

A. ROUGE

B. Word error rate

C. Accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score

D. Edit distance

Answer. C

Lecture 10 – Text Classification with Bag-of-Words and TF-IDF in NLP

Q64. Temporal information extraction focuses on

A. Identifying only locations

B. Detecting time expressions and event ordering in text

C. Compressing large corpora

D. Translating numbers only

Answer. B

Q65. A time expression such as “next week” is best described as

A. Event mention

B. Temporal expression requiring normalization

C. Named entity person

D. Stopword

Answer. B

Q66. Corpus-based methods generally rely on

A. Manually written rules only

B. Statistical patterns learned from large text collections

C. Audio recordings

D. Hardware counters

Answer. B

Q67. Collocation analysis is used to

A. Discover words that co-occur more often than chance

B. Remove punctuation

C. Translate text

D. Measure perplexity

Answer. A

Q68. A distributional semantics approach to corpus-based modelling assumes that

A. Meaning can be inferred from patterns of co-occurrence in corpora

B. Each word must be defined manually

C. Syntax is irrelevant

D. Only labelled data matters

Answer. A

Q69. Temporal ordering of events is important for tasks like

A. Spell checking

B. Timeline extraction and narrative understanding

C. Tokenization

D. POS tagging

Answer. B

Q70. A concordance tool in corpus linguistics shows

A. Only frequency counts

B. Key words with their surrounding context in many sentences

C. Neural network weights

D. Parse trees only

Answer. B

Lecture 9 – Temporal Representations and Corpus Based Methods in Natural Language Processing

Q71. Information retrieval systems primarily return

A. Exact numeric answers

B. Ranked lists of documents or passages

C. Source code

D. Summaries only

Answer. B

Q72. In the vector space model, documents and queries are represented as

A. Trees

B. Real-valued vectors in a common space

C. Audio signals

D. Images

Answer. B

Q73. Cosine similarity between document and query vectors measures

A. Angle between vectors

B. Edit distance

C. Number of stopwords

D. Sentence length

Answer. A

Q74. Precision in IR is

A. Relevant retrieved divided by total relevant documents

B. Relevant retrieved divided by total retrieved documents

C. Total documents divided by relevant documents

D. 1 – recall

Answer. B

Q75. Recall in IR is

A. Relevant retrieved divided by total relevant documents

B. Total retrieved divided by corpus size

C. 1 – precision

D. Always equal to precision

Answer. A

Q76. Indexing in IR mainly involves

A. Building data structures such as inverted indexes for fast retrieval

B. Designing GUIs only

C. Compressing images

D. Parsing all sentences

Answer. A

Lecture 11 – Information Retrieval, Vector Space Model and Evaluation

Q77. Information extraction aims to

A. Translate text

B. Automatically pull structured facts from unstructured text

C. Compress documents

D. Remove stopwords

Answer. B

Q78. Named entity recognition identifies

A. Only verbs

B. Person, organisation, location and similar entities

C. Stopwords

D. HTML tags

Answer. B

Q79. Relation extraction typically outputs

A. Document topics

B. Triples such as (Entity1, Relation, Entity2)

C. Only POS tags

D. Random numbers

Answer. B

Q80. Dependency parses are useful in relation extraction because they

A. Provide character level features

B. Show grammatical relations between words

C. Remove entities

D. Reduce vocabulary

Answer. B

Q81. A knowledge graph is

A. A graph of routers

B. A structured network of entities and relations extracted from data

C. A compression algorithm

D. A POS tagger

Answer. B

Q82. An IE pipeline typically includes

A. Tokenization, NER, parsing, relation extraction

B. Compilation, linking, execution

C. Image segmentation only

D. None of these

Answer. A

Lecture 12 – Information Extraction and Relation Extraction

Q83. Machine translation systems map

A. Images to labels

B. Text from one natural language to another

C. Text to speech

D. Speech to text only

Answer. B

Q84. Rule-based MT systems primarily rely on

A. Manually written linguistic rules and dictionaries

B. Neural networks only

C. Random word substitution

D. Image features

Answer. A

Q85. Phrase-based statistical MT uses

A. Human translation only

B. Probabilities of translating source phrases into target phrases

C. Only character bigrams

D. No corpus at all

Answer. B

Q86. Neural machine translation with encoder-decoder models estimates

A. P(source | target) only

B. P(target | source) directly

C. Perplexity only

D. Edit distance

Answer. B

Q87. Attention in neural MT allows the decoder to

A. Ignore the source sentence

B. Focus on different source positions when generating each target word

C. Reduce vocabulary size

D. Translate only short sentences

Answer. B

Q88. BLEU is mainly used to

A. Train MT models

B. Evaluate machine translation output against reference translations

C. Compress translation memory

D. Detect grammar errors

Answer. B

Lecture 13 – Machine Translation in Natural Language Processing. From Rule Based to Neural

Q89. A question answering system differs from a search engine because it

A. Returns only URLs

B. Tries to return direct answers rather than just documents

C. Ignores the query

D. Works only offline

Answer. B

Q90. Factoid questions generally expect

A. Long essays

B. Lists of unrelated documents

C. Short factual answers such as names or dates

D. Images

Answer. C

Q91. In a classical QA pipeline, which step usually comes first

A. Answer extraction

B. Question analysis

C. Indexing

D. Evaluation

Answer. B

Q92. Reading comprehension QA assumes

A. No passage is given

B. A passage is provided that contains the answer

C. Answer is always “yes” or “no”

D. Only numeric answers

Answer. B

Q93. An open-domain QA system typically needs

A. A large text collection such as Wikipedia

B. Only a single small document

C. Audio recordings

D. Images only

Answer. A

Q94. Neural QA models often operate by

A. Generating random answers

B. Predicting answer spans within retrieved passages

C. Ignoring context

D. Using only rule-based heuristics

Answer. B

Lecture 14 – Question answering in Natural Language Processing

Q95. Extractive summarization works by

A. Generating new sentences from scratch

B. Selecting and concatenating existing sentences from the document

C. Translating the document

D. Counting words

Answer. B

Q96. Abstractive summarization aims to

A. Copy sentences exactly

B. Produce new paraphrased summary sentences

C. Shorten words

D. Remove stopwords only

Answer. B

Q97. TextRank is best described as

A. A neural translation model

B. A graph-based extractive summarization method

C. A smoothing technique

D. An evaluation metric

Answer. B

Q98. ROUGE is commonly used to

A. Evaluate summaries by measuring overlap with reference summaries

B. Train summarization models

C. Compress documents

D. Tag parts of speech

Answer. A

Q99. A key application of text summarization is

A. Generating audio waveforms

B. Producing short versions of news or research papers

C. Parsing sentences

D. Correcting spelling

Answer. B

Q100. One major challenge in abstractive summarization is

A. Lack of neural models

B. Risk of hallucinating content not present in the source

C. Inability to handle any long documents at all

D. Absence of any evaluation metrics

Answer. B

Lecture 15 – Text summarization in Natural Language Processing

B. 30 Short Questions with Brief Answer Points

Q1. What is Natural Language Processing?

Answer: Natural Language Processing is a subfield of Artificial Intelligence and computational linguistics that enables computers to process, analyse and understand human language.

Q2. Give three real-world applications of NLP.

Answer: Typical applications include machine translation, sentiment analysis, speech assistants and chatbots, and email or message spam filtering.

Q3. Why is tokenisation important before most NLP tasks?

Answer: Tokenisation is important because models need discrete units (tokens) such as words or subwords instead of raw character streams to process and represent text.

Q4. What is a standard corpus and why do we use it?

Answer: A standard corpus is a large, curated collection of text (often with annotation) used to train and evaluate NLP models in a consistent and reproducible way.

Q5. Define minimum edit distance between two strings.

Answer: Minimum edit distance is the minimum number of insertions, deletions and substitutions needed to transform one string into another.

Q6. How does a noisy channel model improve spelling correction?

Answer: A noisy channel model improves spelling correction by combining the prior probability of a candidate word from a language model with the error likelihood P(observed∣candidate), and choosing the candidate that maximizes their product.

Q7. What is an n-gram language model?

Answer: An n-gram language model approximates the probability of each word based on the previous n−1 words, using counts of n-grams from a corpus.

Q8. Why do we need smoothing in language models?

Answer: Smoothing is needed to assign non-zero probabilities to unseen n-grams and to improve generalisation of the language model on new data.

Q9. What are the hidden and observed variables in an HMM POS tagger?

Answer: In an HMM POS tagger, the hidden variables are the part-of-speech tags and the observed variables are the words in the sentence.

Q10. What problem does the Viterbi algorithm solve in tagging?

Answer: The Viterbi algorithm finds the single most probable sequence of POS tags for a given sequence of words.

Q11. What is a context-free grammar used for in NLP?

Answer: A context-free grammar is used to define valid sentence structures in a language and to generate parse trees for sentences.

Q12. Differentiate between deterministic and stochastic grammars.

Answer: Deterministic grammars use rules without associated probabilities, while stochastic grammars attach probabilities to rules (as in probabilistic CFGs) to prefer more likely parses.

Q13. What is semantic role labelling?

Answer: Semantic role labelling is the task of identifying roles such as Agent, Patient, Instrument, Location and Time for each predicate in a sentence.

Q14. Give one advantage of vector space meaning representations.

Answer: Vector space meaning representations capture similarity between words or sentences numerically, allowing models to compare and manipulate meanings using algebraic operations.

Q15. What is the goal of sentiment analysis?

Answer: The goal of sentiment analysis is to determine the polarity or emotion expressed in text, typically classifying it as positive, negative or neutral.

Q16. Name two challenges in sentiment analysis on social media.

Answer: Common challenges include informal and noisy language (slang, misspellings, emojis) and phenomena like sarcasm or irony that can flip the apparent sentiment.

Q17. Explain the bag-of-words assumption.

Answer: The bag-of-words assumption represents a document as a multiset of words, ignoring word order and using only word frequencies as features.

Q18. Why is TF-IDF often better than raw term frequency?

Answer: TF-IDF is often better because it downweights very common words across documents and highlights terms that are frequent in a document but rare in the corpus, making them more discriminative.

Q19. What is temporal normalisation?

Answer: Temporal normalisation is the process of mapping expressions like “next Monday” or “yesterday” to precise calendar dates or structured time representations.

Q20. How do corpus-based methods help discover collocations?

Answer: Corpus-based methods discover collocations by analysing co-occurrence statistics of word pairs or n-grams and finding combinations that occur together more often than expected by chance.

Q21. Define precision and recall in IR.

Answer: Precision is the fraction of retrieved documents that are relevant, and recall is the fraction of all relevant documents in the collection that have been retrieved.

Q22. Why do we represent documents as vectors in the vector space model?

Answer: Documents are represented as vectors so that similarity between a query and documents can be computed using measures like cosine similarity for ranking.

Q23. What is the difference between NER and relation extraction?

Answer: Named Entity Recognition finds and labels entity mentions (e.g. person, organisation, location), while relation extraction identifies semantic relations between these entities, such as “born_in” or “works_for”.

Q24. Give an example of a relation triple extracted from text.

Answer: From the sentence “Einstein was born in Ulm”, an example relation triple is (Einstein, born_in, Ulm).

Q25. What is the main difference between phrase-based SMT and neural MT?

Answer: Phrase-based SMT uses explicit phrase tables and a separate language model, whereas neural MT uses an end-to-end encoder–decoder network that directly models the conditional probability of the target sentence given the source.

Q26. Why is attention important in neural MT?

Answer: Attention provides a soft alignment mechanism that allows the decoder to focus on different parts of the source sentence when generating each target word, improving translation quality and handling long sentences.

Q27. What is open-domain question answering?

Answer: Open-domain question answering is QA where questions can be about almost any topic, and the system searches a large corpus such as Wikipedia or the web to find answers.

Q28. What are the three main stages in a classic IR-based QA pipeline?

Answer: The three stages are question analysis, document or passage retrieval and answer extraction.

Q29. What is the key difference between extractive and abstractive summarization?

Answer: Extractive summarization selects and concatenates existing sentences or phrases from the source text, while abstractive summarization generates new paraphrased sentences to express the main ideas.

Q30. Why is ROUGE commonly used in summarization evaluation?

Answer: ROUGE is commonly used because it measures n-gram and sequence overlap between system-generated summaries and human reference summaries as a proxy for how much important content is preserved.

C. 15 Long / Theory Questions (with expected points)

Q1. Explain the evolution of Natural Language Processing from rule-based systems to statistical and neural approaches. Discuss key milestones and how availability of corpora and computing power changed typical NLP architectures?

Early NLP systems were rule-based and symbolic. Linguists and knowledge engineers manually wrote grammars, lexicons and if–then rules to analyse and generate sentences. Systems such as early machine translation prototypes or expert systems relied on hand-crafted morphology rules, phrase structure rules and pattern matching. These approaches could be very precise in narrow domains, but they were brittle, hard to scale and extremely expensive to maintain because every new phenomenon needed new rules.

In the 1990s, the field shifted towards statistical NLP. Large digital corpora became available and researchers started to model language using probabilities learned from data. Typical milestones include n-gram language models for speech recognition and spelling correction, Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) for part-of-speech tagging and probabilistic context-free grammars for parsing. Later, statistical machine translation (SMT) based on word and phrase alignment replaced many rule-based MT systems. The availability of corpora like the Penn Treebank and large parallel corpora, together with faster CPUs, made these models practical.

From around 2010 onwards, NLP entered the neural era. Distributed word embeddings such as word2vec and GloVe represented words as dense vectors that capture semantic similarity. Recurrent neural networks, LSTMs and later sequence-to-sequence models with attention achieved strong results in translation, summarization and many other tasks. With further increases in computing power and GPUs, very large transformer-based models like BERT, GPT and similar architectures became standard. These models are pre-trained on huge text corpora and then fine-tuned on specific tasks, dramatically improving performance across POS tagging, parsing, QA, sentiment, MT and more.

Overall, the evolution from rule-based to statistical to neural NLP has been driven by the availability of large corpora and computing power. Architectures moved from hand-crafted symbolic rules, to probabilistic models estimated from corpora, to deep neural networks pre-trained on web-scale data. Modern NLP systems are therefore much more robust, data-driven and adaptable than early rule-based systems.

Q2. Describe the complete text preprocessing pipeline used before training an NLP model. Include tokenization, normalization, stopword removal, stemming or lemmatization, and handling of punctuation, numbers and emojis. Why is consistent preprocessing crucial when building corpora?

Before training any NLP model, raw text must pass through a preprocessing pipeline. The first stage is usually tokenisation, where continuous text is split into tokens such as words or subwords. For English, tokenisation handles spaces, punctuation and contractions. The next step is normalisation, for example converting text to lowercase, standardising quotation marks, expanding common abbreviations, or handling Unicode variants.

After that, many pipelines apply stopword removal. Very frequent function words like “the”, “is”, “of” often carry little discriminatory power for tasks such as classification, so they may be removed. Next comes stemming or lemmatisation. Stemming crudely strips suffixes to obtain word stems (e.g. “running”, “runs” → “run”), while lemmatisation uses vocabulary and morphological analysis to map inflected forms to dictionary lemmas. This reduces vocabulary size and helps the model share statistics across related forms.

Preprocessing must also decide how to handle punctuation, numbers and emojis. Some tasks keep punctuation as separate tokens because it signals sentence boundaries or sentiment, while others remove it. Numbers may be kept, normalised (e.g. replacing all digits with a special token) or split into components. In social media text, emojis and hashtags often carry strong sentiment or topic signals, so they are either preserved as tokens or mapped to special categories.

Consistent preprocessing is crucial. The same steps must be applied to both training and test data, otherwise the model will see different token distributions at test time and performance will drop. Preprocessing also affects the vocabulary: different tokenization or normalization choices produce different token sets and frequency counts, which change TF-IDF features, language model statistics and embeddings. Using standard, documented pipelines ensures reproducibility of experiments and fair comparison of models across research groups. For corpus building, recording exact preprocessing steps is therefore an essential part of good experimental practice.

Q3. Define minimum edit distance and derive the dynamic programming recurrence for computing Levenshtein distance between two strings. Illustrate the algorithm on a small example and explain how this distance is used in spelling correction?

Minimum edit distance between two strings is defined as the minimum number of editing operations required to transform one string into the other, where operations are typically insertion, deletion and substitution of single characters. In Levenshtein distance, each operation usually has cost 1, and matching characters have cost 0.

To compute this efficiently, we use dynamic programming. Suppose we want the distance between strings s of length m and t of length n. We create a table D of size (m+1) × (n+1) where D[i][j] is the minimum cost to transform the first i characters of s into the first j characters of t.

Base cases.

D[0][0] = 0(empty to empty).D[i][0] = i(i deletions to turn s[1…i] into empty).D[0][j] = j(j insertions to turn empty into t[1…j]).

Recurrence for i>0, j>0.

Let cost = 0 if s[i] == t[j], otherwise cost = 1. Then

D[i][j] = min( D[i-1][j] + 1, # deletion D[i][j-1] + 1, # insertion D[i-1][j-1] + cost ) # substitution or match

For example, consider s = "cat" and t = "cut". The distance is 1 because replacing a by u turns “cat” into “cut”. The DP table will reflect that only one substitution is needed. For a slightly longer example such as “kitten” → “sitting”, the optimal sequence is two substitutions (k→s, e→i) and one insertion (g), giving distance 3.

In spelling correction, minimum edit distance is used to generate candidate corrections. Given a misspelled word, the system finds all dictionary words within a small edit distance (e.g. 1 or 2). Among these candidates, the system can then choose the best correction using a language model and a noisy channel formulation: pick the candidate w that maximizes P(w) × P(observed | w). Minimum edit distance helps approximate the error probability P(observed | w) and efficiently enumerate plausible candidates. Thus, dynamic programming for edit distance is a core building block in many spell checkers.

Q4. What is a language model Explain n-gram language models, the Markov assumption, and the need for smoothing and backoff. Discuss how perplexity is computed and why it is a useful evaluation metric?

A language model assigns probabilities to sequences of words, such as P(w₁, w₂, …, wₙ). It captures how likely sentences are in a language and is used in tasks like speech recognition, spelling correction and machine translation. Directly modelling full history is intractable, so n-gram language models use the Markov assumption: the probability of a word depends only on the previous n−1 words. For a trigram model,

P(w₁…wₙ) ≈ ∏ P(wᵢ | wᵢ₋₂, wᵢ₋₁)

This approximation makes estimation feasible from corpora by counting n-grams. However, data sparsity is a major issue. Many n-grams are unseen even in large corpora, leading to zero probabilities.

To address this, we use smoothing. Smoothing methods, such as add-one (Laplace) smoothing, Good–Turing or Kneser–Ney, redistribute some probability mass from seen n-grams to unseen ones. Backoff models combine different n-gram orders: if a trigram is rare or unseen, we “back off” to a bigram or unigram probability, often with weights ensuring total probability remains 1. Smoothing and backoff are crucial for producing robust language models that handle novel sequences.

To evaluate language models, we often use perplexity. For a test set of N words with true sequence probability P(w₁…w_N) under the model, perplexity is

PP = P(w₁…w_N)^(-1/N) = exp( - (1/N) ∑ log P(wᵢ | history) )

Intuitively, perplexity measures how “confused” the model is; lower perplexity indicates better predictive performance. On the same test set, a model with lower perplexity is generally considered a better language model. Thus, n-gram factorization, smoothing/backoff and perplexity form the foundation of classical statistical language modelling.

Q5. Explain the structure of a Hidden Markov Model for part-of-speech tagging. Discuss transition and emission probabilities, training using tagged corpora, and decoding using the Viterbi algorithm with a worked mini example?

A Hidden Markov Model (HMM) for part-of-speech (POS) tagging assumes that each word in a sentence is generated by a hidden POS tag. The hidden states are POS tags such as Noun, Verb, Adjective, and the observations are the surface words.

The model is specified by:

- Transition probabilities

P(tᵢ | tᵢ₋₁)describing how likely one tag follows another. For example,P(Verb | Noun)may be high if verbs often follow nouns. - Emission probabilities

P(wᵢ | tᵢ)describing how likely a tag emits a particular word. For example,P("run" | Verb)andP("run" | Noun)capture different uses of “run”. - Initial tag probabilities

P(t₁)for sentence starts.

These parameters are estimated from a tagged corpus by counting tag bigrams and word–tag pairs, then normalising to obtain probabilities.

Given a new sentence, we want the most probable tag sequence t₁…tₙ given the observed words w₁…wₙ. The Viterbi algorithm solves this efficiently using dynamic programming. It maintains a table V[i][t] equal to the maximum probability of any tag sequence ending in tag t at position i. The recurrence is:

V[i][t] = max_{t'} ( V[i-1][t'] × P(t | t') × P(wᵢ | t) )

We also store backpointers to reconstruct the best path.

For a mini example, consider the two-word sentence “Time flies”. Possible tags for “Time” are Noun or Verb, and for “flies” Noun or Verb. Using learned transition and emission probabilities, the Viterbi algorithm will compute scores for sequences such as Noun–Verb (“Time” as Noun, “flies” as Verb) or Verb–Noun. In English, corpora often make Noun–Verb more probable in this context, so the HMM tagger will output that sequence. Thus, HMMs with Viterbi decoding provide a principled probabilistic framework for resolving POS ambiguity.

CMU Neural Natural Language Processing course notes and slides

Q6. Describe context-free grammars and probabilistic CFGs. Compare top-down and bottom-up parsing strategies and outline how dynamic programming algorithms such as CYK parse a sentence efficiently?

A context-free grammar (CFG) defines the syntactic structure of a language using:

- A set of nonterminals (e.g. S, NP, VP).

- A set of terminals (words).

- A start symbol (often S).

- A set of production rules such as

S → NP VPorVP → V NP.

These rules generate parse trees that show how sentences are built from phrases. However, many sentences have multiple possible parse trees, leading to ambiguity.

A probabilistic context-free grammar (PCFG) extends CFGs by attaching a probability to each production rule, such as P(VP → V NP | VP). The probability of a parse tree is the product of its rule probabilities. PCFGs allow us to rank alternative parses and choose the most likely one given observed usage in a treebank.

Parsing strategies include top-down and bottom-up parsing. Top-down parsing starts from the start symbol and tries to expand to match the sentence, which may explore many impossible derivations. Bottom-up parsing starts from the words and builds up larger constituents, but may build structures that do not lead to a complete parse.

Dynamic programming algorithms like CYK (Cocke–Younger–Kasami) parse more efficiently by filling a chart of possible constituents for each span of the sentence. CYK requires the grammar in Chomsky Normal Form. For a sentence of length n, we create a triangular table where each cell (i, j) stores which nonterminals can derive the substring from position i to j. Rules are applied bottom-up, combining smaller spans into larger ones. This approach avoids redundant work and runs in O(n³ × |G|), where |G| is grammar size.

Thus, CFGs and PCFGs provide a formal foundation for syntactic analysis, while parsing strategies and algorithms like CYK make parsing practical for real sentences.

Q7. What is semantic role labelling Explain how predicate–argument structure is represented, give examples of common roles (Agent, Patient, Instrument, Location, Time), and discuss how syntactic information such as parse trees helps in predicting semantic roles?

Semantic role labelling (SRL) is the task of identifying the roles that different sentence constituents play with respect to a predicate, usually a verb. It aims to capture “who did what to whom, where, and when”. This is often called predicate–argument structure.

For example, in the sentence “The student submitted the assignment yesterday”:

- Predicate: “submitted” (the action).

- Agent (or Experiencer): “The student” – the doer of the action.

- Patient / Theme: “the assignment” – the entity affected by the action.

- Time: “yesterday” – when the action occurred.

Other common roles include Instrument (tool used), Location, Beneficiary and so on. These roles can be formalised using frames or semantic templates, where each frame defines expected roles for a particular type of event (e.g. COMMERCIAL_TRANSACTION frame with Buyer, Seller, Goods, Money).

SRL systems rely heavily on syntactic information such as parse trees. The constituent structure and dependency relations help locate arguments relative to the predicate. For instance, the subject NP of a transitive verb is often the Agent, and the direct object NP is often the Patient or Theme. Prepositional phrases introduced by “in”, “on”, “at”, “with”, “to” may be mapped to roles like Location, Instrument or Goal depending on context.

Features used in SRL include the phrase type of the candidate argument (NP, PP), its position relative to the predicate, the dependency path between them and lexical information like the verb lemma. Machine learning or neural models then learn to assign role labels based on these features.

SRL has important applications in information extraction and question answering. It allows systems to move from surface strings to structured representations of events and participants, enabling more precise extraction of who did what and better semantic matching of questions and answers.

Q8. Define sentiment analysis and discuss rule-based, lexicon-based and machine learning based approaches. Explain major challenges such as domain dependency, sarcasm and class imbalance, and how model evaluation is performed?

Sentiment analysis is the task of automatically determining the attitude or opinion expressed in text, typically classifying it as positive, negative or neutral. It is widely used for product reviews, social media monitoring and brand analysis.

There are three main families of approaches.

- Rule-based methods use hand-crafted rules to look for polarity cues. For example, they may increase a sentiment score when they see words like “good”, “excellent” and decrease it for “bad”, “terrible”, adjusting for negation (“not good”) or intensifiers (“very good”).

- Lexicon-based methods rely on sentiment lexicons: dictionaries that assign prior polarity scores to words or phrases. The sentiment of a text is computed by aggregating the scores of words, perhaps weighted by frequency or position, again with rules for negation, intensification and contrast.

- Machine learning-based methods treat sentiment classification as a supervised text classification problem. Bag-of-words, n-grams, embeddings or transformer representations are fed into classifiers such as Naive Bayes, SVM, logistic regression or neural networks. Deep models (e.g., BiLSTMs, CNNs, transformers) can capture more complex contextual sentiment patterns.

Several challenges complicate sentiment analysis. Domain dependency means that words may change polarity depending on context (e.g. “unpredictable” is good for a movie plot but bad for a car). Sarcasm and irony can invert sentiment even when positive words are used (“Great, my phone died again”). Short informal texts with slang, emojis and misspellings also make analysis harder. Class imbalance is common when one sentiment class dominates the data.

For evaluation, standard classification metrics are used: accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score, often computed per class or macro-averaged. Confusion matrices help reveal which classes are confused. For fine-grained or ordinal sentiment (e.g. star ratings), correlation measures or mean squared error may be used. Overall, good sentiment models must combine robust features with strategies to handle domain variation and figurative language.

Practical NLP exercises with code – Hugging Face course

Q9. Explain the bag-of-words model and TF-IDF weighting for text classification. Compare Naive Bayes and Logistic Regression classifiers for document classification, including their assumptions, advantages and limitations.?

The bag-of-words (BoW) model represents a document by the frequencies of its words, disregarding order. Each document becomes a high-dimensional vector where each dimension corresponds to a vocabulary term and the value is its count. Although simple, this representation often works well for text classification tasks like spam detection or topic classification.

TF-IDF weighting refines BoW by balancing term frequency (TF) with inverse document frequency (IDF). TF captures how often a word appears in a document; IDF downweights words that appear in many documents and therefore carry little discriminative power. The TF-IDF weight is often TF × IDF. This highlights terms that are frequent in a given document but rare in the corpus, making them more useful for distinguishing classes.

Two common classifiers for text are Naive Bayes and Logistic Regression. Naive Bayes is a generative model: it estimates P(word | class) from training data under the assumption that words are conditionally independent given the class. Then it uses Bayes’ rule to compute P(class | document) and chooses the class with maximum posterior probability. Its advantages are simplicity, fast training and surprisingly good performance on high-dimensional sparse text features. However, the independence assumption is unrealistic and can limit accuracy.

Logistic Regression is a discriminative model: it directly models P(class | features) using a linear combination of feature weights passed through a sigmoid (for binary) or softmax (for multi-class) function. It does not assume feature independence and can learn more flexible decision boundaries. It often achieves higher accuracy than Naive Bayes when sufficient training data is available but may require more careful regularisation. Both models can be extended with n-gram features, but Logistic Regression tends to benefit more from correlated features because it can assign interacting weights.

In summary, BoW and TF-IDF provide standard feature representations, Naive Bayes offers a simple and fast baseline, and Logistic Regression often delivers better performance at the cost of more complex training.

Q10. Discuss temporal information extraction from text. Describe how temporal expressions are detected and normalized, how events and their ordering are modelled, and mention applications such as building timelines from news corpora?

Temporal information extraction focuses on identifying time-related information and event ordering in text. It involves three main tasks: detecting temporal expressions, normalising them to a standard format and modelling temporal relations between events.

Temporal expressions (TIMEXes) include explicit dates (“12 March 2024”), relative expressions (“yesterday”, “next week”), durations (“for three months”) and frequencies (“every Monday”). Detection is usually done using a combination of pattern matching and machine learning.

Temporal normalisation maps these expressions to structured representations, often based on standards like ISO 8601. For example, “yesterday” must be resolved with respect to a document creation time; “next Monday” must be mapped to a specific calendar date. This step is essential for aligning events on a common timeline.

Events themselves are identified using trigger words such as verbs (“arrived”, “announced”) or eventive nouns (“explosion”, “election”). Once events and time expressions are detected, the system determines temporal relations such as BEFORE, AFTER, INCLUDES or SIMULTANEOUS. These relations can hold between events, between events and times, or between times themselves. Machine learning models often use features from syntax, tense and aspect, temporal signals (“before”, “since”), and the position of expressions in the text.

Applications of temporal IE include building timelines from news, tracking patient histories in clinical narratives, analyzing trends in social media and supporting question answering about when events occurred. Challenges include resolving vague or underspecified expressions, dealing with narrative reordering (flashbacks), and handling cross-document event coreference. Despite these difficulties, temporal IE is crucial for turning unstructured text into structured chronological information.

Q11. Describe the vector space model for information retrieval. Explain how documents and queries are represented, how cosine similarity is computed, and how precision, recall and F1 are used to evaluate retrieval quality?

In the vector space model (VSM) for information retrieval, documents and queries are represented as vectors in a high-dimensional space, typically using TF-IDF weights. Each dimension corresponds to a vocabulary term, and the value reflects its importance in that document or query. This allows retrieval to be framed as finding documents whose vectors are similar to the query vector.

Cosine similarity is a common measure of similarity between document vector d and query vector q. It is defined as:

cos(θ) = (d · q) / (||d|| × ||q||)

where d · q is the dot product and ||d|| and ||q|| are the Euclidean norms. Cosine similarity ranges from 0 to 1 for non-negative vectors and measures the angle between them, focusing on direction rather than magnitude. Documents are ranked by decreasing cosine similarity to the query.

To evaluate retrieval quality, we use precision, recall and F1.

- Precision = (number of relevant documents retrieved) / (total documents retrieved). It measures how many retrieved documents are actually relevant.

- Recall = (number of relevant documents retrieved) / (total relevant documents in the collection). It measures how many of the relevant documents we successfully found.

- F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing the two:

F1 = 2 × (precision × recall) / (precision + recall)

There is usually a trade-off: systems tuned for high precision may be conservative and miss some relevant documents (lower recall), while systems tuned for high recall may return many irrelevant documents (lower precision). Evaluation often uses precision–recall curves or measures like average precision to summarize ranking quality. Together, VSM with cosine similarity and these evaluation metrics form the classical foundation of modern search engines.

Q12. What is information extraction Describe the main components of an IE system including tokenization, NER, parsing and relation extraction. Explain how the output of IE can be used to build knowledge graphs and support downstream tasks like question answering?

Information extraction (IE) is the task of automatically pulling structured facts from unstructured text. An IE system typically follows a pipeline with several components.

- Tokenisation and sentence segmentation break documents into sentences and tokens.

- Named Entity Recognition (NER) identifies mentions of entities such as persons, organisations, locations, dates and numeric quantities. For example, “Albert Einstein”, “Ulm” and “1879” are recognised and labelled.

- Parsing provides syntactic structure through dependency or constituency trees, describing how words relate grammatically.

- Relation extraction identifies semantic relations between entities, such as (Person, born_in, Location) or (Company, acquired, Company). This can be done using patterns over dependency paths, supervised classifiers or neural models.

The output of IE can populate a schema with entity types and relation types. From many documents, we can build a knowledge graph where nodes represent entities and edges represent relations. For instance, a biographical graph might connect “Albert Einstein” to “Ulm” via “born_in” and to “Physics” via “field_of_work”.

These structured representations support downstream tasks like question answering. Instead of searching raw text, QA systems can query the knowledge graph directly: “Where was Einstein born” becomes a graph query retrieving the location linked by born_in. Even when QA still uses text passages, IE-based features help rank answer candidates.

Thus, IE transforms large text corpora into interconnected structured data, enabling more powerful analytics, search and reasoning across domains such as news, scientific literature and enterprise documents.

Q13. Compare rule-based, statistical and neural approaches to machine translation. Highlight their architectures, strengths and weaknesses, and describe the role of attention and BLEU evaluation in modern neural MT?

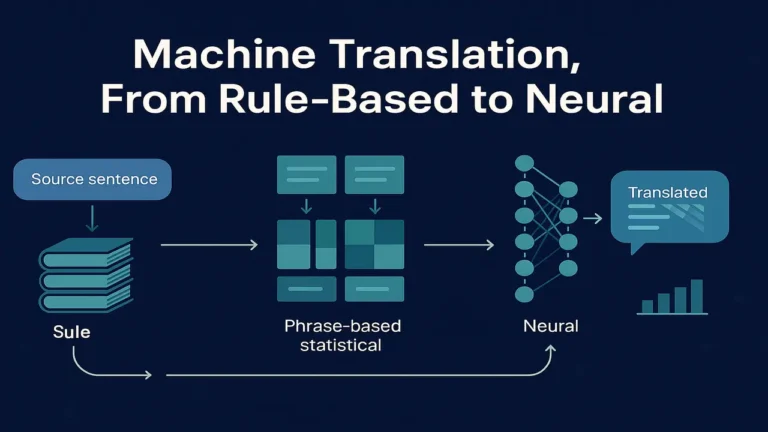

Rule-based machine translation (RBMT) systems rely on hand-crafted linguistic rules and bilingual dictionaries. They perform deep analysis of source sentences (morphology, syntax, semantics), transfer these structures to target representations and then generate target sentences. RBMT can produce high-quality translations in controlled domains with well-developed grammars, but it is labour-intensive to build, hard to adapt to new language pairs and struggles with idioms and data-driven variations.

Statistical machine translation (SMT) replaced rules with probabilities learned from parallel corpora. Word-based SMT models learned alignment probabilities between source and target words, while phrase-based SMT used phrase pairs and a log-linear combination of features including translation probabilities and a target language model. Decoding searched for the most probable target sentence given the source. SMT handles many phenomena better than RBMT and is easier to adapt when parallel data is available, but it produced translations that sometimes lacked fluency and coherence at the sentence level.

Neural machine translation (NMT) uses encoder–decoder architectures, typically with recurrent or transformer networks. The encoder converts the source sentence into contextual embeddings; the decoder generates the target sentence token by token, modelling P(target | source) directly. NMT captures long-range dependencies better and often produces more fluent, natural output than SMT, especially with large training data.

Attention mechanisms are central in modern NMT. Instead of compressing the entire source into a single vector, attention allows the decoder to dynamically focus on different source positions when generating each target word. This provides soft alignments and improves translation quality, especially for long sentences or complex reordering.

For evaluation, BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy) is widely used. It compares MT output to one or more human reference translations by measuring the precision of overlapping n-grams, with a brevity penalty for overly short outputs. Higher BLEU scores indicate closer overlap. However, BLEU has limitations: it does not account well for synonyms or paraphrases, and high BLEU does not guarantee human-level quality. Despite this, BLEU remains a standard automatic metric for comparing MT systems.

In summary, MT has evolved from rule-based systems with strong linguistic knowledge but limited coverage, to statistical phrase-based models, to end-to-end neural models with attention and better fluency, evaluated primarily with metrics such as BLEU.

Q14. Explain the architecture of an information retrieval based question answering system. Detail the stages of question analysis, document/passage retrieval and answer extraction, and discuss how neural QA models modify or replace parts of this pipeline?

An information retrieval-based question answering (QA) system aims to return direct answers to user questions by combining search and NLP. Its architecture typically has three main stages.

- Question analysis. The system tokenises the question, performs POS tagging and parsing, and applies named entity recognition. A crucial step is question classification or answer type detection: for example, recognising that “Who” questions expect a person, “Where” questions expect a location, and “When” questions expect a date. The system also identifies key content words to be used in retrieval.

- Document or passage retrieval. The analysed question is converted into a search query and sent to an IR engine (often using a vector space model with TF-IDF or BM25). The engine retrieves a ranked list of documents or passages (e.g. paragraphs or sentences) that are likely to contain the answer. Passage retrieval narrows down the search space for answer extraction.

- Answer extraction. Over the top retrieved passages, the QA system searches for candidate answer spans. It can use NER to find entities of the expected answer type, pattern matching on dependency structures, or other heuristics linking question terms to text segments. Each candidate span is scored based on features such as match with question terms, proximity to key words and passage rank. The highest scoring span is returned as the answer, often with a supporting snippet and document link.

Modern neural QA models modify or enhance this pipeline. In reading comprehension style QA, a neural model such as a transformer takes the question and a given passage as input and directly predicts start and end indices of the answer span. In open-domain QA, systems use a retrieve-and-read architecture: an IR or dense retriever first selects candidate passages from a large corpus like Wikipedia, then a neural reader model processes each passage with the question to extract answers. Scores are aggregated to choose the best overall answer.

In some setups, neural models can even generate free-form answers rather than marking spans, especially when integrated with large language models and tools. Nonetheless, the core ideas of question analysis, retrieval and answer extraction remain, with neural components replacing or augmenting earlier rule-based and statistical modules.

Q15. Discuss extractive and abstractive text summarization in detail. Explain graph-based methods such as TextRank, sequence-to-sequence neural summarization, and evaluation with ROUGE metrics. Mention typical use cases and key challenges such as redundancy and hallucination?

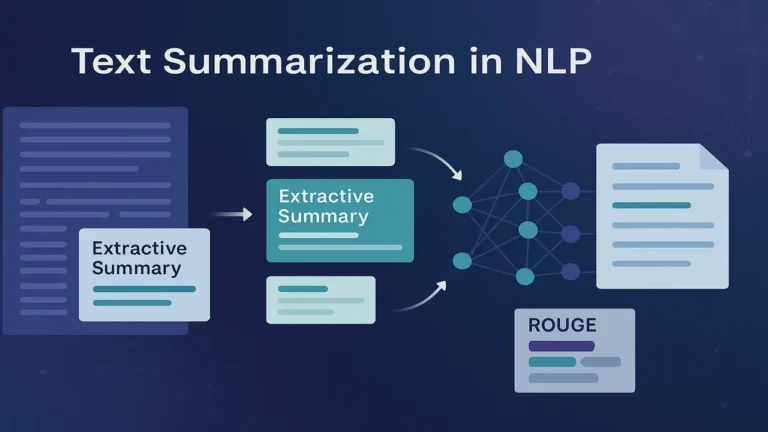

Text summarization aims to produce a shorter text that preserves the main ideas of a longer document. There are two main paradigms: extractive and abstractive summarization.

In extractive summarization, the system selects important sentences or phrases directly from the source document and concatenates them to form the summary. It does not generate new text. Importance can be determined using features such as sentence position, TF-IDF scores, similarity to the document title or presence of named entities. Extractive methods are relatively simple, maintain grammaticality and are widely used in practice. However, they may include redundant content and cannot easily merge or compress information from multiple sentences.

Graph-based methods like TextRank provide a powerful unsupervised approach to extractive summarization. Sentences are represented as nodes in a graph, and edges are weighted by similarity (e.g. cosine similarity over TF-IDF vectors). A ranking algorithm similar to PageRank runs a random walk over this graph, assigning high scores to sentences that are central and strongly connected to other important sentences. The top-ranked sentences are then selected as the summary, often with additional constraints to reduce redundancy.

In abstractive summarization, the system generates new sentences that may paraphrase, compress or fuse information across the document. Neural sequence-to-sequence models with attention treat summarization like translation from long text to short text. An encoder reads the document and produces contextual representations; a decoder with attention and often copy mechanisms generates the summary word by word. This allows more human-like summaries but introduces risks of hallucination, where the model invents facts not present in the source. Abstractive models also face challenges handling very long inputs.

For evaluation, ROUGE metrics are commonly used. ROUGE-N measures recall of overlapping n-grams between a system summary and one or more human reference summaries. ROUGE-1 uses unigrams, ROUGE-2 uses bigrams. ROUGE-L uses longest common subsequence. Higher ROUGE scores indicate that the system summary captures more of the content present in reference summaries. However, ROUGE does not fully reflect coherence, readability or factual correctness, so human evaluation is still important.

Typical applications of summarization include news and blog summarization, research paper summarization, contract and legal document summarization, meeting minutes and customer support ticket summaries. Key challenges remain: controlling redundancy, maintaining coherence across multiple sentences, avoiding hallucinated content and evaluating summaries beyond surface n-gram overlap.