How CPU caches work: locality, set mapping, write policies, replacement, TLB, prefetching, and how to measure cache performance in practice.

Locality & AMAT

- Temporal and spatial locality keep working sets hot.

- AMAT ≈

HitTime + MissRate × MissPenalty.- Reduce any of the three to speed up memory performance.

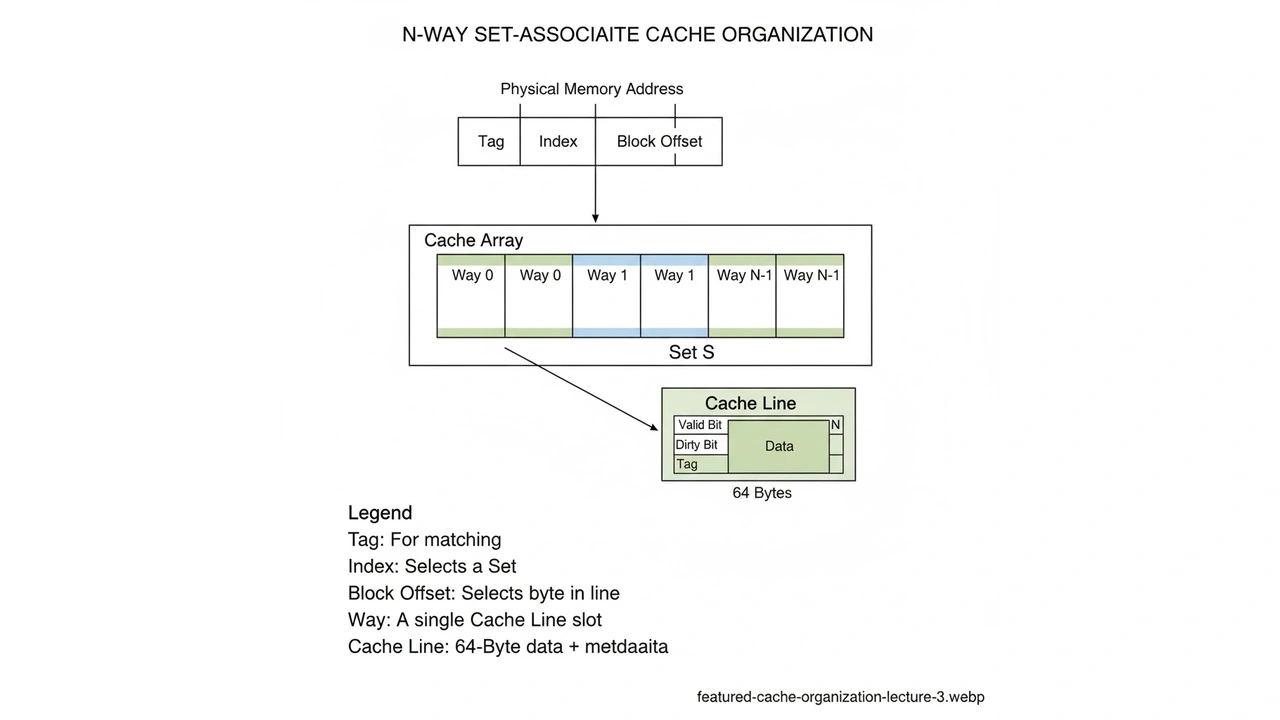

Cache Organization

- Line (block) size: commonly 64 B; too small → more misses; too large → more waste/conflicts.

- Direct-mapped: 1 line per set (fast, but conflict-prone).

- N-way set-associative: compromise; typical 4–16 ways.

- Fully associative: any line anywhere (expensive hardware).

- Index/Tag/Offset:

- Offset selects a byte within the line, Index selects the set, Tag confirms identity.

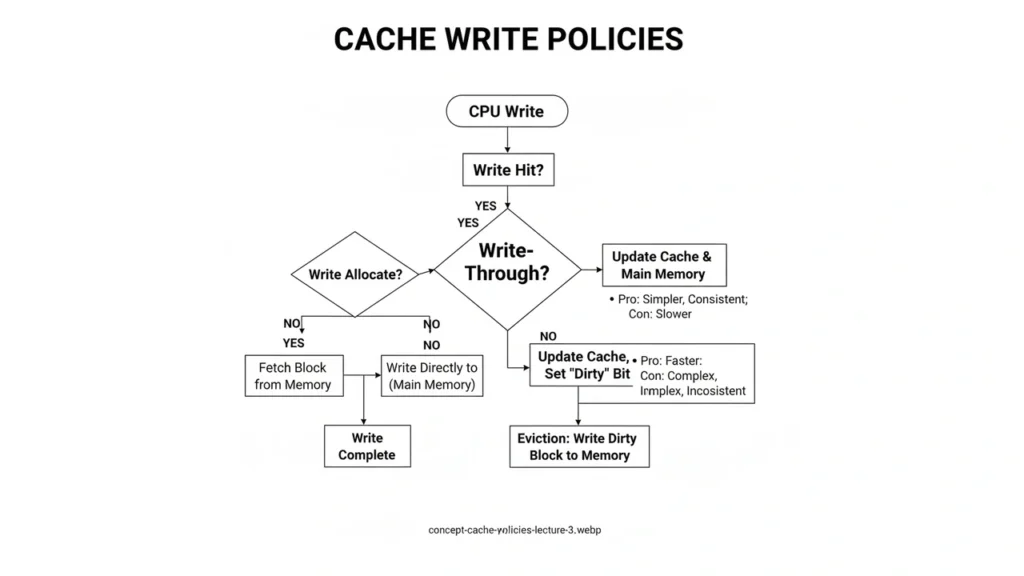

Replacement & Write Policies

- Replacement: LRU (or PLRU) tends to minimize conflict misses; random is cheap and often good enough.

- Write-through: update cache + memory immediately; simpler coherence, more bandwidth.

- Write-back: update cache only; mark dirty and write on eviction; saves bandwidth, needs dirty tracking.

- Write-allocate: on a write miss, bring the line in, then write.

- No-write-allocate: write around the cache (common with write-through).

The TLB Connection

- Each memory reference first needs virtual→physical translation.

- TLB caches recent translations; a TLB miss triggers a page table walk.

- Performance rule: good cache behavior can still be slow with TLB thrashing (e.g., huge random working sets); consider huge pages where appropriate.

Prefetching

- Sequential prefetch helps streaming reads; stride prefetch helps regular steps.

- Bad prefetch = extra traffic + pollution. Evaluate with counters/benchmarks.

Measuring Cache Behavior (Lab)

# Python/Numpy microbench (run as a script or in a notebook)

import numpy as np, time, os

N = 128*1024*1024 // 8 # 128 MB as int64

a = np.zeros(N, dtype=np.int64)

def scan(stride):

s = 0; t = time.time()

for i in range(0, N, stride):

s += a[i]

return time.time()-t, s

for stride in [1,2,4,8,16,32,64,128,256,512,1024,4096]:

t, s = scan(stride)

print(f"stride={stride:4d} time={t:6.3f}s sum={s}")Quick Check (with answers)

- Why does larger line size improve streaming but hurt random access? More spatial locality captured, but more useless bytes fetched (pollution).

- Which policy reduces write traffic to DRAM? Write-back.

- What causes a conflict miss? Two or more hot addresses mapping to the same set/line.

- Why can TLB misses slow an otherwise cache-friendly loop? Every access still needs a translation; TLB thrash adds page walks.

- What does AMAT stand for? Average Memory Access Time.

The approach followed at E Lectures reflects both academic depth and easy-to-understand explanations.

People also ask:

Not always hardware is costlier and slower. Many designs use 8–16 ways for last-level caches.

When simplicity and data reliability are more important than raw bandwidth (e.g., small caches, MMIO regions).

They reduce TLB pressure but can increase memory waste and complicate allocation; use for large, contiguous working sets.

Grow array sizes (capacity) or change strides/alignments (conflict). If adding associativity fixes it, it was conflict-driven.

Linux perf, Intel VTune, AMD uProf, Apple Instruments, plus hardware counters via perf stat -e cache-misses,cache-references.