Core concepts of automata alphabets, strings, languages, operations (union, concatenation, Kleene star), and proof methods explained with clear examples and tasks.

Introduction

Automata theory starts with precise building blocks: alphabets, strings, and languages. We use these to describe patterns, build machines that recognize them, and prove properties about what machines can or cannot do. This first lecture sets the foundation you’ll reuse in regular expressions (RE), finite automata (FA), pushdown automata (PDA), and Turing machines (TM).

Alphabets, Strings, and Languages

- Alphabet (Σ): A finite, nonempty set of symbols.

Examples: Σ = {0,1}, Σ = {a,b}, Σ = {a,…,z}. - String (word): A finite sequence of symbols from Σ.

Example over {0,1}:0101. - Empty string (ε): String of length 0.

- Length (|w|): Number of symbols in w. Example: |0101| = 4.

- Kleene star (Σ*): The set of all finite strings over Σ, including ε.

- Language (L): Any set of strings over Σ.

Example: L = { w ∈ {a,b}* : w has an even number of a’s }.

Tiny check: Is ε in Σ*? Yes, always. Is ε necessarily in every language L? Not unless defined that way.

Operations on Languages

Let L₁ and L₂ be languages over the same Σ:

- Union: L₁ ∪ L₂ = { w : w ∈ L₁ or w ∈ L₂ }

- Concatenation: L₁·L₂ = { xy : x ∈ L₁, y ∈ L₂ }

- Kleene Star: L* = { ε, w, ww, www, … | w ∈ L }

- Complement (relative to Σ*): L̅ = Σ* \ L

- Reverse: L^R = { w^R : w ∈ L } where (

abc)^R =cba

Quick example: If L = {0,01} over {0,1}, then L* includes ε, 0, 01, 00, 001, 010, 0101, … and so on.

Three Ways to Describe a Language

- Informally: “All binary strings with an even number of 1s.”

- Set-builder: L = { w ∈ {0,1}* : the number of 1s in w is even }.

- By examples/non-examples: ε, 0, 00, 11, 1010 ∈ L; 1, 01, 111 ∉ L.

Getting fluent at switching between these descriptions makes later transformations (like RE ↔ NFA ↔ DFA) much easier.

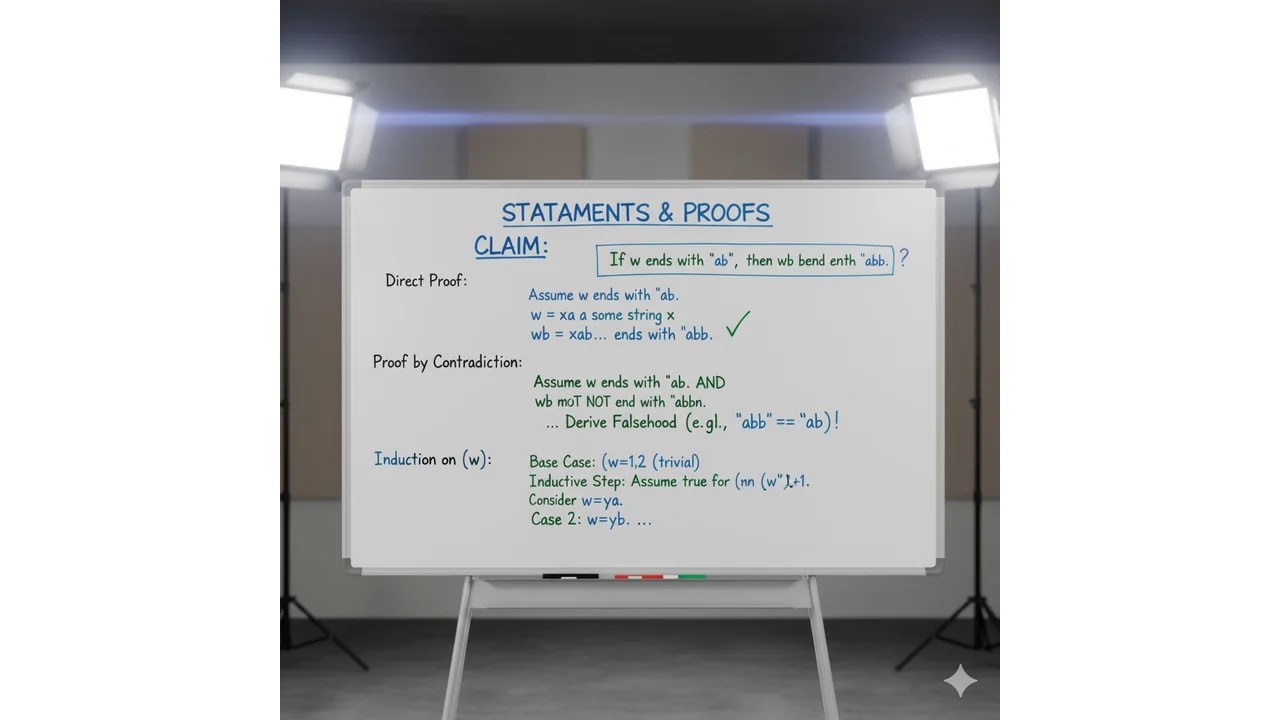

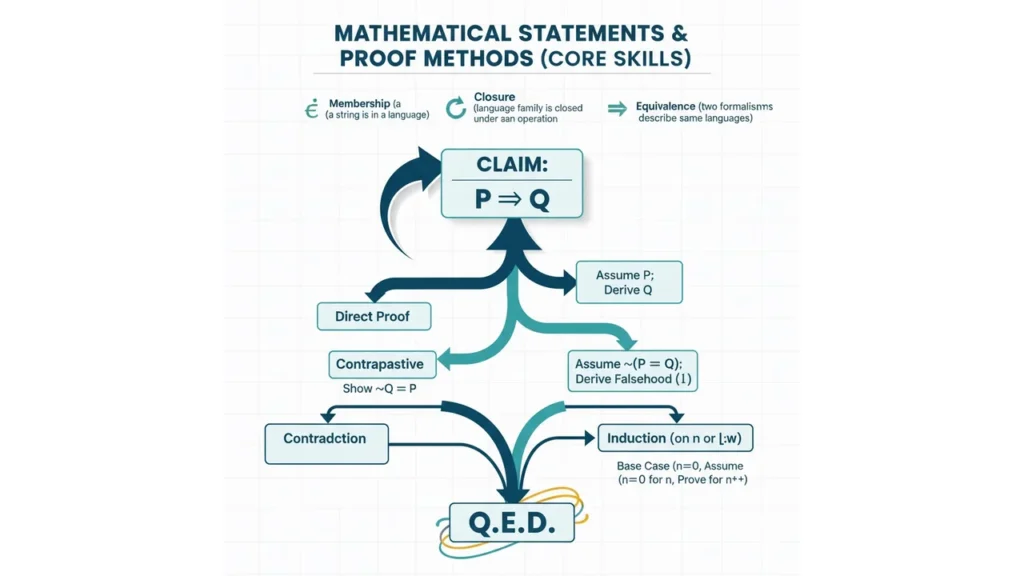

Statements and Proof Methods (Core Skills)

A mathematical statement is a precise claim that is either true or false. In this course, statements often assert:

- Membership (a string is in a language),

- Closure (a language family is closed under an operation),

- Equivalence (two formalisms describe the same set of languages).

Main proof techniques you’ll use:

- Direct Proof: Assume premises, derive the conclusion step by step.

- Contrapositive: To prove

P ⇒ Q, show¬Q ⇒ ¬P. - Contradiction: Assume the claim is false and derive a contradiction.

- Induction (on n or |w|): Prove the base case; then assume the claim for n and prove it for n+1.

Mini Examples

- Direct Proof (string property):

Claim: If a string w over {a,b} ends withab, thenw bends withabb.

Proof idea: The last two symbols of w areaandb. Appending anotherbmakes the last threeabb. Q.E.D. - Induction (length reasoning):

Claim: Over Σ={a}, every string is a^n for some n≥0.

Base: ε = a^0.

Step: If w = a^n, then wa = a^(n+1). Hence every string in Σ* has the form a^n.

These patterns scale up to closure proofs, correctness of constructions, and later to undecidability arguments.

Why This Foundation Matters

- We will design DFAs for simple patterns, prove they are minimal, and show equivalence with NFAs and regular expressions.

- We will prove some languages are not regular using the pumping lemma.

- We will define CFGs and PDAs and show connections between them.

- We will build simple Turing machines and discuss what is decidable or undecidable.

Quick Practice (Do Now)

- Let Σ = {a,b}. List all strings of length ≤ 2.

- Define L = “strings ending with

ab” in set-builder notation. - If L₁ = {a, ab} and L₂ = {b}, list L₁·L₂.

- Write an informal and formal definition for “strings over {0,1} with an odd number of 0s.”

- Sketch a contradiction proof idea for: “There is no last string in {a}* under the length order.”

Common Pitfalls

- Confusing ε (the empty string) with ∅ (the empty set).

- Forgetting that Σ* always contains ε.

- Mixing up string reversal and language reversal.

- Writing informal claims without clear quantifiers or scope.

- Using induction but skipping the base case or not stating the inductive hypothesis clearly.

The approach followed at E Lectures reflects both academic depth and easy-to-understand explanations.

Summary and Next Steps

You now have the core language needed to speak automata: alphabets, strings, languages, operations, and the proof tools you’ll use all semester. Next, we move to Regular Expressions and Finite Automata, and we will start constructing recognizers for useful language families.

People also ask:

A finite, nonempty set of symbols, for example {0,1} or {a,b,c}.

ε is always in Σ*, but it belongs to a specific language L only if L includes it by definition.

A string is a single sequence of symbols. A language is a set of strings.

They justify correctness of constructions (like DFAs) and global properties (closure, equivalence, decidability).

Use induction when a statement is naturally indexed by size—string length, number of steps, or number of states.

Repeated concatenation of strings from a language, including zero repetitions (ε).

Yes. Most languages of interest (like all strings with an even number of 1s) are infinite subsets of Σ*.

Once we can describe languages precisely, we build machines (DFAs/NFAs) that recognize them and prove which families of languages they capture.