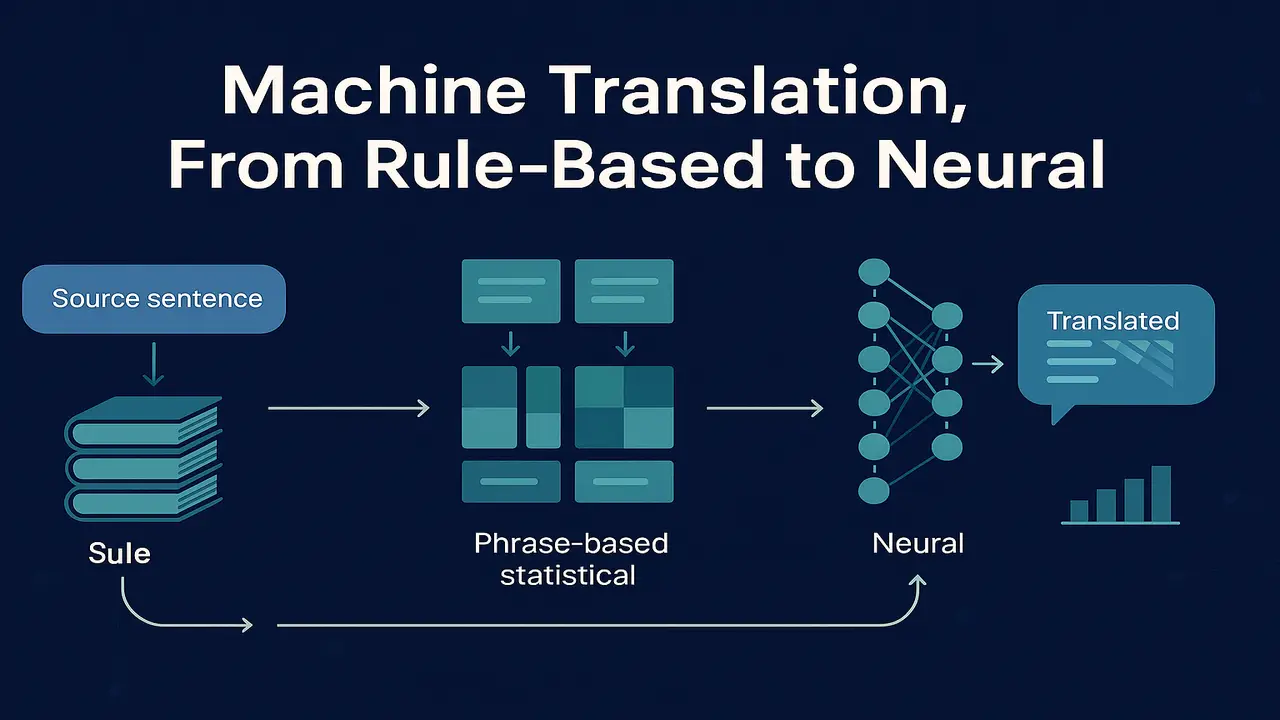

How machine translation evolved from rule based and statistical methods to modern neural MT with attention.

Automatic translation of human languages is one of the oldest and most ambitious goals in Natural Language Processing. Decades before deep learning, researchers tried to design systems that could translate between English, Russian, French and many other languages using hand written rules and dictionaries. Later, statistical methods replaced manual rules with probabilistic models learned from bilingual corpora. Today, neural machine translation with encoder decoder architectures and attention dominates both research and industry.

This lecture gives a conceptual tour of machine translation in NLP. We start with classical rule based and phrase based statistical systems, introduce the idea of alignment between words and phrases, then move to high level neural MT with encoder decoder networks and attention. Finally, we discuss BLEU as a widely used automatic evaluation metric and highlight its intuition and limitations.

What is machine translation in NLP

Machine translation aims to automatically convert a sentence or document from a source language into a target language while preserving meaning and producing fluent, grammatical output. The input might be a news article, a technical manual, a product description or a social media comment.

Formally, for each source sentence x we want to generate a target sentence y that is both adequate (correct meaning) and fluent (natural in the target language). Unlike many NLP tasks, there is rarely a single correct output. Several valid translations may exist with different wording but similar meaning. This makes both modelling and evaluation more challenging.

From an NLP perspective, machine translation is interesting because it requires:

. strong language models in both source and target languages

. models of cross lingual correspondence between words, phrases and syntactic structures

. algorithms that search over a huge space of possible translations

Earlier lectures on language modelling, parsing and representation directly support this task.

Lecture 4 – Language Modeling in Natural Language Processing

Classical rule based machine translation

Early MT systems were primarily rule based. Linguists and engineers wrote large sets of rules describing:

. morphology and syntax of the source language

. morphology and syntax of the target language

. transfer rules mapping source structures to target structures

The pipeline often looked like this.

- Analyse the source sentence with a morphological analyser and parser.

- Convert the resulting structure into an abstract interlingua or into a target oriented syntactic structure using transfer rules.

- Generate the target sentence using morphological rules and a realisation grammar.

Advantages.

. Rule based systems can enforce strong grammaticality in constrained domains.

. They provide interpretable representations and can handle rare words with explicit rules.

Limitations.

. Rule sets are labour intensive to construct and maintain.

. Coverage is limited. language is full of idioms, exceptions and domain specific usages.

. Adapting to new language pairs or new domains requires major manual effort.

Because of these issues, the field gradually shifted toward corpus based and statistical methods that learn patterns directly from data.

Statistical machine translation and alignment

Statistical Machine Translation (SMT) treats translation as a probabilistic decision problem. Given a source sentence x, we look for the target sentence y that maximises a probability model P(y | x).

The classic noisy channel formulation factorises this as:

P(y | x) ∝ P(x | y) P(y)

where:

. P(y) is a language model over target sentences, often an n gram model like those studied in Lecture 4.

. P(x | y) is a translation model telling us how likely the source sentence is, given a hypothesised target sentence.

The key insight is that if we have a large parallel corpus of sentence pairs, we can statistically estimate how words and phrases in one language tend to correspond to words and phrases in the other.

This leads to the idea of alignment. For each sentence pair, we can imagine links between source words and target words that translate each other. For example:

“the black cat” ↔ “le chat noir”

Alignment might link “the” ↔ “le”, “black” ↔ “noir”, “cat” ↔ “chat”. Real examples are more complex because word order differs and some words have no direct counterpart.

Early SMT models, such as the IBM word alignment models, use expectation maximization to infer word to word alignment probabilities from large bilingual corpora. Phrase based SMT later generalized this to sequences of words (phrases) rather than individual words, allowing better handling of local reordering and idioms.

Phrase based SMT in simple terms

Phrase based SMT became the dominant approach before neural methods. Its translation pipeline can be described conceptually as follows:

- From the parallel corpus, extract many bilingual phrase pairs. contiguous sequences of words in the source aligned to sequences in the target.

- Estimate probabilities for each phrase pair, such as P(target phrase | source phrase).

- Train an n gram language model over the target language.

- During decoding, segment the source sentence into phrases, choose translations for each phrase and reorder them to form a fluent target sentence.

The final decision is made by a log linear model that combines several feature scores:

. phrase translation probabilities

. lexical translation probabilities

. language model score

. penalties for distortion (reordering) and phrase count

A beam search or stack decoder explores candidate translations and selects the one with the highest global score.

Although phrase based SMT achieved impressive results compared to earlier rule based systems, it has several weaknesses:

. It relies on local phrase context and shallow language models, making long range dependencies difficult to capture.

. It struggles with complex agreement phenomena and rich morphology.

. Many separate components must be tuned carefully.

These limitations opened the door for end to end neural approaches.

For a detailed, textbook-level overview of rule-based, statistical and neural machine translation, see the machine translation chapter in Speech and Language Processing by Jurafsky and Martin.

Neural machine translation. encoder decoder idea

Neural Machine Translation (NMT) replaces separate translation and language models with a single neural network that directly estimates P(y | x). Conceptually, it uses an encoder decoder architecture.

- The encoder reads the source sentence and converts it into a sequence of continuous vector representations. In early models this was a recurrent neural network; later models use transformers.

- The decoder generates the target sentence one token at a time, conditioning on its own previous outputs and on the encoded representation of the source.

- At each step, the decoder outputs a probability distribution over the target vocabulary. The translation is obtained by choosing the most likely sequence, typically with beam search.

Intuitively, the encoder maps the source sentence into a semantic representation, while the decoder learns how to express that meaning in the target language using a strong neural language model.

Advantages of NMT.

. Handles long range dependencies more naturally than phrase based SMT.

. Jointly learns translation and language modelling in one system.

. Produces more fluent output, especially with large training data.

. Learns distributed word and phrase representations that generalise across similar contexts.

Challenges include the need for large amounts of parallel data, difficulty with rare words and a tendency to produce fluent but occasionally hallucinated translations if the input is out of domain.

Attention mechanism. intuition only

Early encoder decoder models compressed the entire source sentence into a single fixed size vector, which limited performance on long sentences. The attention mechanism solves this by allowing the decoder to look back at different parts of the source sequence when generating each target word.

High level view.

- For each source position, the encoder produces a hidden state vector.

- At a given decoding step, the model computes a set of attention weights over these encoder states based on how relevant each source position is to the current decoding context.

- These weights form a soft alignment, and a weighted sum of encoder states creates a context vector that guides the next word prediction.

This means the decoder no longer relies on a single compressed representation. Instead, it dynamically focuses on different source words as needed, similar to how human translators shift their attention along the sentence.

Transformers generalize this idea with multi head self attention and cross attention layers throughout the network, enabling very powerful sequence to sequence models.

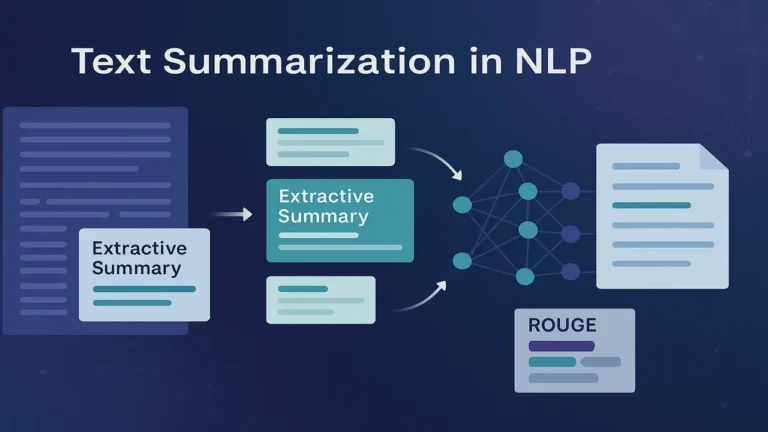

Evaluation of machine translation. BLEU intuition

Evaluating machine translation is tricky because many correct translations exist. Human evaluation, where bilingual judges rate adequacy and fluency, is the gold standard but expensive. For large scale experiments, we use automatic metrics such as BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy).

BLEU compares the system output against one or more human reference translations, focusing on overlapping n grams. The key components are:

. modified n gram precision. counts how many 1,2,3,4 gram segments in the candidate appear in the references, with clipping to avoid rewarding repetition.

. brevity penalty. discourages overly short translations that might have high precision by copying only a subset of words.

The BLEU score is roughly the geometric mean of n gram precisions multiplied by the brevity penalty. Intuitively, a high BLEU score means the system output shares many n gram fragments with at least one human translation and has a similar length.

Limitations.

. BLEU is insensitive to synonyms and paraphrases that differ in wording but have similar meaning.

. It works best when multiple reference translations are available.

. As a corpus level metric, it can be misleading for very short test sets.

Nevertheless, BLEU remains widely used as a quick proxy for translation quality in research papers and benchmarks.

Real examples of machine translation

You can present these briefly as concrete scenarios.

- Web page translation. Browsers integrate neural MT engines to translate entire websites from English to Urdu, French, Arabic or any other language in a single click.

- Product description localisation. E commerce platforms translate thousands of product titles and descriptions into local languages to increase conversions without writing each one manually.

- Customer support. Companies translate incoming emails and chat messages into a single pivot language for support agents, then translate replies back to the customer’s language.

- Real time speech translation. Meeting tools combine automatic speech recognition with NMT to provide subtitles in multiple languages during live calls.

- Low resource language support. Research prototypes use transfer learning and multilingual NMT to support languages with limited parallel data by leveraging related high resource languages.

Step by step algorithm explanation (phrase based SMT decoding)

For conceptual clarity, here is a simplified phrase based SMT decoding algorithm.

Step 1. Preprocess the source sentence and segment it into tokens.

Step 2. Using the phrase table learned from the parallel corpus, find all possible source phrase spans and their candidate target phrase translations with associated probabilities.

Step 3. Initialize a beam with an empty partial translation and a coverage vector marking which source words have been translated.

Step 4. Repeatedly extend partial translations by selecting an untranslated source phrase, appending a candidate target phrase to the hypothesis and updating the coverage vector.

Step 5. For each hypothesis, compute a combined score using.

. phrase translation log probabilities

. target language model score for the growing target sentence

. distortion penalties for large jumps in source phrase order

. bias terms such as word and phrase count penalties

Step 6. Keep only the top scoring hypotheses in the beam at each step to control search complexity.

Step 7. When all source words are covered, select the highest scoring complete hypothesis as the final translation.

Although modern systems use neural decoders, the idea of balancing translation likelihood, language model fluency and structural constraints through search remains central.

Code examples (simple demonstration in Python)

Below is a very small illustrative example that shows how one might call a pre trained neural MT model using the Hugging Face transformers library. This is just demonstration code for students; it assumes the relevant packages and model weights are installed.

from transformers import AutoModelForSeq2SeqLM, AutoTokenizer

# Load a pre-trained English-to-German translation model

model_name = "Helsinki-NLP/opus-mt-en-de"

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_name)

model = AutoModelForSeq2SeqLM.from_pretrained(model_name)

def translate_en_to_de(sentence: str, max_length: int = 60) -> str:

# Encode the input sentence

inputs = tokenizer(sentence, return_tensors="pt")

# Generate translation with beam search

outputs = model.generate(

**inputs,

max_length=max_length,

num_beams=4,

early_stopping=True

)

# Decode tokens to text

return tokenizer.decode(outputs[0], skip_special_tokens=True)

if __name__ == "__main__":

src = "Machine translation is an important application of natural language processing."

print("Source:", src)

print("German:", translate_en_to_de(src))Summary

Machine translation in NLP has travelled a long path. from hand crafted rule based systems and phrase based statistical models built on alignment and n gram language models to powerful neural encoder decoder architectures with attention. Each generation of models brought improvements in fluency, adequacy and adaptability while also introducing new challenges such as data requirements and evaluation.

Understanding this evolution is important for students because it reveals how advances in representation, modelling and computation changed what was possible in translation. Language models, alignment, attention and evaluation metrics like BLEU are not isolated topics. together they form the backbone of modern translation engines that millions of people use every day.

Next Lecture 14 – Question Answering Systems in NLP

People also ask:

Machine translation in NLP is the automatic conversion of text from one human language to another while preserving meaning and producing fluent output. It uses linguistic knowledge, statistical models and modern neural networks to map source sentences to target sentences.

Early systems relied on hand written linguistic rules and dictionaries. Later, statistical machine translation used bilingual corpora to learn word and phrase correspondences combined with n gram language models. Today, neural machine translation uses encoder decoder networks with attention to model translation end to end and typically outperforms earlier approaches.

Language models estimate how likely a sequence of words is in the target language. In statistical MT they are a separate component that encourages fluent output. In neural MT they are integrated into the decoder, which learns simultaneously to model target language fluency and to condition on the source sentence.

Attention allows the decoder to focus on different parts of the source sentence when generating each target word. Instead of compressing the source into a single vector, the model computes a weighted combination of encoder states based on their relevance, creating a dynamic soft alignment between source and target tokens.

BLEU is an automatic metric that compares system translations with one or more human reference translations by measuring n gram overlap and applying a brevity penalty. Higher BLEU scores indicate closer matches to the references, although the metric does not perfectly capture meaning and fluency and should ideally be complemented by human evaluation.