Natural Language Processing systems almost never receive perfectly clean and error free input. Users type quickly on mobile phones. Optical character recognition introduces mistakes when scanning documents. Search queries are full of missing letters, extra letters and swapped characters. Any system that works with text at scale must therefore be able to judge how similar two strings are and to suggest corrections when necessary.

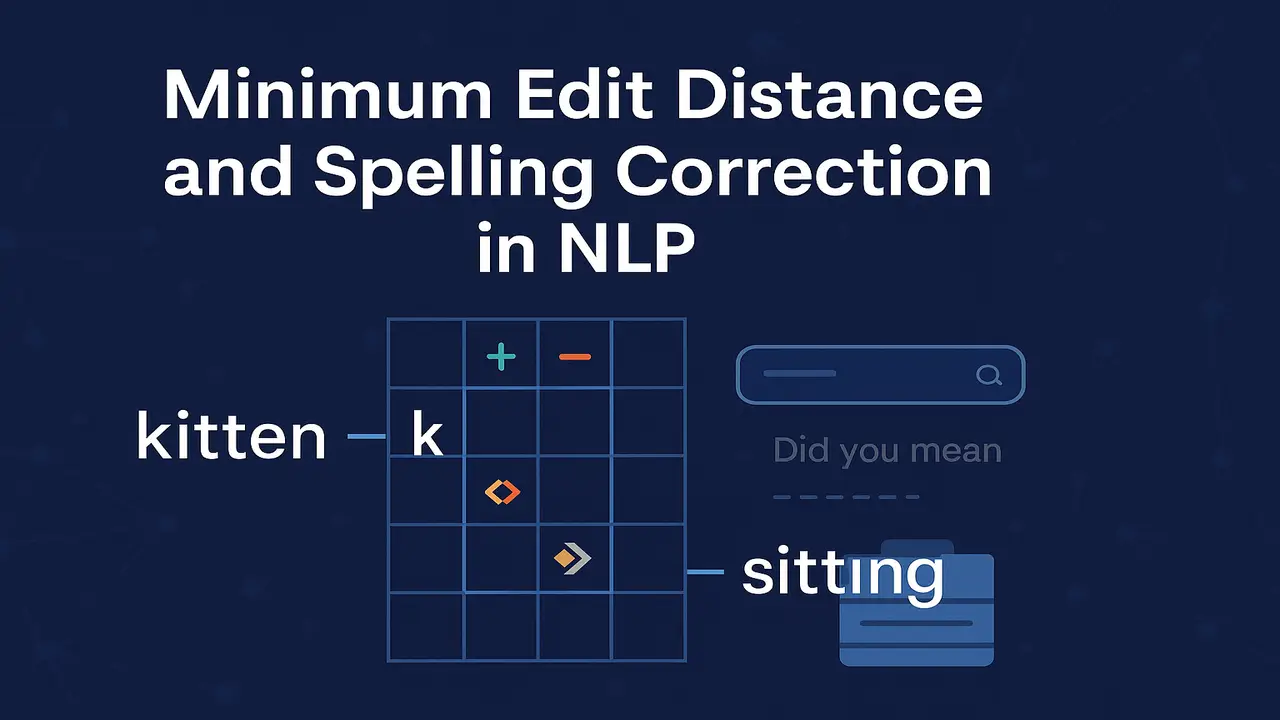

Minimum edit distance is one of the most fundamental tools for measuring similarity between strings. It provides a clear and mathematically grounded way to ask how many operations are required to transform one word into another. Combined with language models and frequency information, it becomes the core of many spelling correction systems in search engines, text editors and messaging applications.

This lecture develops a solid understanding of minimum edit distance, explains the dynamic programming algorithm used to compute it and shows how it connects to practical spelling correction. The emphasis is on clear intuition, step by step reasoning and concrete examples that can be implemented in Python.

String Similarity and Spelling Errors

When a user types a word incorrectly, the misspelling is often not completely unrelated to the intended word. Instead, it is close in terms of small mistakes.

- Letters may be missing. example. enviroment instead of environment.

- Extra letters may appear. example. commitee instead of committee.

- Some letters may be wrong. example. computor instead of computer.

- Letters may be swapped. example. teh instead of the.

Intuitively these errors feel small. It should be possible to define a numerical measure that captures this smallness. Minimum edit distance provides such a measure by counting how many basic operations are needed to turn one string into another.

Edit Operations and Cost Model

Minimum edit distance is defined in terms of simple edit operations applied to characters of a string. The classical formulation uses three operations.

- Insertion. Insert a character into the string.

- Deletion. Delete a character from the string.

- Substitution. Replace one character with another.

A cost is associated with each operation. The simplest and most common choice is to assign cost 1 to each insertion, deletion and substitution and cost 0 to keeping a character unchanged. Under this model the minimum edit distance between two strings is the minimal total cost of any sequence of operations that transforms the source string into the target string.

For some applications different costs are useful. Substituting a nearby key on the keyboard may be more likely than substituting a distant key, so the cost of that substitution could be lower. Deleting or inserting vowels might be cheaper than consonants in some languages. Such extensions are known as weighted or non uniform edit distance. In this lecture the focus is on the basic uniform cost version, sometimes called Levenshtein distance.

Example. Distance Between Kitten and Sitting

A classic example illustrates the idea clearly. Consider the words kitten and sitting. One possible sequence of edits is the following.

- Substitute s for k at the beginning. kitten becomes sitten.

- Substitute i for e near the end. sitten becomes sittin.

- Insert g at the end. sittin becomes sitting.

This sequence uses two substitutions and one insertion, for a total cost of 3 when all costs are 1. It is natural to ask whether a cheaper sequence exists. In this case it can be shown that 3 is indeed the minimum possible cost, so the minimum edit distance between kitten and sitting is 3.

The example shows that the distance captures our intuitive feeling that the words are fairly similar. It also highlights the need for a systematic method to be sure that the minimal cost sequence has been found. This is where dynamic programming enters.

Dynamic Programming Formulation

Computing minimum edit distance by simply generating all possible sequences of edits would be impossible for anything but very short strings. Instead, a dynamic programming approach breaks the problem into smaller subproblems with overlapping structure.

Suppose the source string is written as s with length m and the target string as t with length n. Consider the prefix of s up to position i and the prefix of t up to position j. Define a matrix D of size m plus 1 by n plus 1, where D at i, j represents the minimum edit distance between the first i characters of s and the first j characters of t.

The matrix is filled according to three simple ideas.

- The first row and first column correspond to converting prefixes into an empty string or vice versa, which requires only insertions or deletions.

- Any cell D at i, j can be reached from three neighbouring cells representing the three possible last operations.

- The cost at D at i, j is the minimum of the three possibilities.

More concretely.

- Initialise D at 0, 0 to 0.

- For each i from 1 to m set D at i, 0 equal to i. This corresponds to deleting i characters.

- For each j from 1 to n set D at 0, j equal to j. This corresponds to inserting j characters.

For the main recurrence, when i is greater than 0 and j is greater than 0, compute.

- Deletion cost. D at i minus 1, j plus cost of deleting s at position i. usually 1.

- Insertion cost. D at i, j minus 1 plus cost of inserting t at position j. usually 1.

- Substitution or match cost. If s at i equals t at j, cost is D at i minus 1, j minus 1. If they differ, cost is D at i minus 1, j minus 1 plus substitution cost usually 1.

Then D at i, j is the minimum of these three quantities.

When the matrix is completely filled, the minimum edit distance between the full strings s and t is given by D at m, n.

Manual Computation on a Small Example

Consider computing the distance between intention and execution. For illustration, a shorter example such as cat and cut is easier.

Let s be cat and t be cut. The lengths are m equals 3 and n equals 3. The matrix D has 4 by 4 entries.

- Initialise first row. D at 0,0 equals 0, D at 0,1 equals 1, D at 0,2 equals 2, D at 0,3 equals 3.

- Initialise first column. D at 1,0 equals 1, D at 2,0 equals 2, D at 3,0 equals 3.

Now fill the interior cells.

- For i equals 1, j equals 1. compare c and c. They match.

- Deletion cost. D at 0,1 plus 1 equals 2.

- Insertion cost. D at 1,0 plus 1 equals 2.

- Match cost. D at 0,0 equals 0.

So D at 1,1 equals 0.

- For i equals 1, j equals 2. compare c and u. They differ.

- Deletion cost. D at 0,2 plus 1 equals 3.

- Insertion cost. D at 1,1 plus 1 equals 1.

- Substitution cost. D at 0,1 plus 1 equals 2.

Minimum is 1, so D at 1,2 equals 1.

- For i equals 1, j equals 3. compare c and t. They differ.

Deletion cost is 4, insertion cost is 2, substitution cost is 3. The minimum is 2, so D at 1,3 equals 2.

Continuing this process for all cells eventually yields D at 3,3 equals 1. The distance between cat and cut is 1, which matches our intuition that only one substitution is needed.

Working through such an example carefully helps students to see how the recurrence relation in the dynamic programming algorithm corresponds directly to the possible edit operations.

Lecture 2 – Text Preprocessing and Standard Corpora in Natural Language Processing

Weighted Edit Distance and Keyboard Errors

The basic algorithm can be extended by adjusting the costs of different operations. This is especially valuable in spelling correction where some mistakes are more common than others.

For example, on a QWERTY keyboard, the letters m and n are adjacent. The substitution of m for n may be more frequent and therefore assigned a lower cost such as 0 point 5. The substitution of q for p, which are far apart, may remain at cost 1. Similarly, errors that insert or delete repeated letters in words like letter and leter might be considered cheaper than other insertions or deletions.

To support such variations, the dynamic programming algorithm only needs to modify how costs are looked up when computing deletion, insertion and substitution. Instead of using a constant cost of 1, it consults a cost function that depends on the specific characters involved. The overall structure of the matrix and the recurrence remains the same.

Spelling Correction using Minimum Edit Distance

Minimum edit distance becomes truly useful when combined with a dictionary of valid words and a model of how common each word is. A typical spelling correction system for single words follows three main steps.

Step 1. Candidate generation. Given a possibly misspelled word w, generate a set of candidate words from the dictionary that are within a certain maximum edit distance, such as 1 or 2.

Step 2. Candidate scoring. For each candidate c, compute a score that combines.

- The edit distance between w and c.

- The frequency or prior probability of c in a corpus.

Candidates with lower edit distance and higher frequency are preferred.

Step 3. Selection. Choose the candidate with the highest overall score as the suggested correction.

In many systems the score is based on a noisy channel model. The user intends a correct word c, which passes through a noisy channel such as a keyboard and produces observed word w. The system attempts to find the most likely intended word given the observed input. This perspective nicely integrates minimum edit distance as a model of the channel and language models as priors.

In practice, additional constraints are used. For example, if the input matches a known word exactly, no correction is needed. If the word appears inside a larger sentence, nearby context words may help decide between alternatives. For example, the word peace is more likely than piece after the phrase world.

Real World Examples of Spelling Correction

Several everyday scenarios demonstrate the importance of minimum edit distance.

Example. Search engine query correction. When a user types enviroment policy, the search engine detects that enviroment is not a common word in its index. It searches for dictionary words at small edit distance and finds environment as a strong candidate. It also sees that environment occurs very frequently in its logs and documents. As a result, it shows a suggestion such as Did you mean environment policy.

Example. Word processors and office suites. When a writer types seperate instead of separate, the spell checker underlines the word in red. It relies on minimum edit distance to propose separate as an alternative because the edit distance is small and the frequency of separate is high.

Example. Mobile keyboards. On touch screens, users often hit neighbouring keys. If a user types goid instead of good, the minimum edit distance to good is low and the keyboard has strong evidence from previous user behaviour that good is more common. It automatically corrects the input or offers good as a suggestion.

Example. Optical character recognition of scanned documents. When characters are misread due to low quality scans, the resulting text contains many near misspellings. Post processing with dictionary based correction using edit distance can substantially improve quality, especially for common words.

These examples illustrate that minimum edit distance is not an abstract theoretical measure. It appears in almost any system that needs to correct or interpret imperfect text input.

Step by Step Algorithm Summary

The dynamic programming algorithm for minimum edit distance can be summarised in a clear sequence of steps.

Step 1. Let the source string be s of length m and the target string be t of length n. Create a matrix D with m plus 1 rows and n plus 1 columns.

Step 2. Initialise the first row. Set D at 0, j equal to j for all j from 0 to n. This corresponds to transforming an empty prefix of s into the first j characters of t by j insertions.

Step 3. Initialise the first column. Set D at i, 0 equal to i for all i from 0 to m. This corresponds to transforming the first i characters of s into an empty string by i deletions.

Step 4. For each cell D at i, j where i is at least 1 and j is at least 1, compute three intermediate values.

- Deletion. D at i minus 1, j plus deletion cost.

- Insertion. D at i, j minus 1 plus insertion cost.

- Substitution or match. If s at i equals t at j, use D at i minus 1, j minus 1. If they differ, use D at i minus 1, j minus 1 plus substitution cost.

Step 5. Set D at i, j equal to the minimum of these three values.

Step 6. After filling the entire matrix, read the minimum edit distance from D at m, n.

Step 7. Optionally recover an explicit sequence of edits by backtracking from D at m, n to D at 0, 0, at each step moving to the neighbour that gave the minimal cost. This produces a human readable explanation of the edits.

This algorithm runs in time proportional to m times n, which is efficient enough for short strings such as individual words and short phrases.

Python Code Examples

The following Python function implements the simple uniform cost minimum edit distance algorithm using the dynamic programming matrix described above.

def edit_distance(s, t):

m = len(s)

n = len(t)

# Create (m+1) x (n+1) matrix

D = [[0] * (n + 1) for _ in range(m + 1)]

# Initialise first row and first column

for i in range(m + 1):

D[i][0] = i # deletions

for j in range(n + 1):

D[0][j] = j # insertions

# Fill the matrix

for i in range(1, m + 1):

for j in range(1, n + 1):

deletion = D[i - 1][j] + 1

insertion = D[i][j - 1] + 1

if s[i - 1] == t[j - 1]:

substitution = D[i - 1][j - 1] # no cost

else:

substitution = D[i - 1][j - 1] + 1

D[i][j] = min(deletion, insertion, substitution)

return D[m][n]A tiny test demonstrates its behaviour.

print(edit_distance("kitten", "sitting")) # expected 3

print(edit_distance("cat", "cut")) # expected 1

print(edit_distance("intention", "execution")) # classic exampleFor a very simple spelling suggestion system, one can combine this function with a small vocabulary.

def suggest_correction(word, vocabulary, max_distance=2):

best_candidate = None

best_distance = max_distance + 1

for candidate in vocabulary:

d = edit_distance(word, candidate)

if d < best_distance:

best_distance = d

best_candidate = candidate

return best_candidate

vocab = ["cat", "cut", "cute", "cot", "coat", "cart"]

print(suggest_correction("ct", vocab)) # likely "cat" or "cut"

print(suggest_correction("cuut", vocab)) # likely "cut" or "cute"This is of course only a toy. Real systems use larger vocabularies and incorporate word frequencies and context, but the underlying distance computation is the same.

Summary

Minimum edit distance provides a clean and powerful way to compare strings and to model the small changes caused by human typing errors, OCR noise and other imperfect input processes. By defining simple operations such as insertion, deletion and substitution and assigning costs to them, it becomes possible to compute the smallest number of edits required to transform one string into another.

The dynamic programming algorithm for minimum edit distance is efficient and conceptually elegant. It underpins many practical spelling correction systems, especially when combined with dictionaries and language models. Real applications in search engines, text editors, mobile keyboards and OCR pipelines rely on this concept every day, often without users realising it.

With a strong understanding of edit distance, students are better prepared to study related topics such as approximate string matching, noisy channel models, language modelling and robust information retrieval, which will appear in the following lectures of the course.

Next. Lecture 4 – Language Modeling, N-grams, Smoothing and Backoff in NLP.

People also ask:

Minimum edit distance is a measure of how different two strings are, defined as the minimum total cost of insertions, deletions and substitutions required to transform one string into the other. It is widely used in spelling correction, string matching and approximate search.

Spelling errors are usually small changes to the correct word. Minimum edit distance quantifies how close a misspelled word is to each candidate in a dictionary. Combined with word frequency information, it allows a system to suggest the most likely intended word.

Levenshtein distance is a specific form of edit distance where insertion, deletion and substitution all have cost 1 and matches have cost 0. General edit distance allows different weights for different operations or pairs of characters, which can better model keyboard layouts or language specific error patterns.

No. While it is most commonly introduced with examples on single words, the same concept can be applied to phrases, short sentences, DNA sequences and any other sequences of symbols. For longer texts, however, other similarity measures and models are often more efficient.

The standard algorithm runs in time proportional to the product of the lengths of the two strings. For typical word lengths this is very efficient. For very long sequences, optimizations and approximate methods can be used, but for single word spelling correction the classic algorithm is more than fast enough.