.

15 core security design principles least privilege, defense in depth, fail-safe defaults, and more with practical checklists and real examples.

Why Security Design Principles Matter

Security failures rarely come from one bug they come from design shortcuts. Principles give teams a shared compass so decisions stay secure before code is written and after deployment. They reduce attack surface, improve auditability, and make incidents containable.

The 15 Principles (with examples)

1) Least Privilege

Give every user, process, and service only the permissions it needs no more.

Dev example: database user with SELECT on read-only paths; admin actions behind a separate role.

Ops example: scoped cloud IAM roles; no wildcard * permissions.

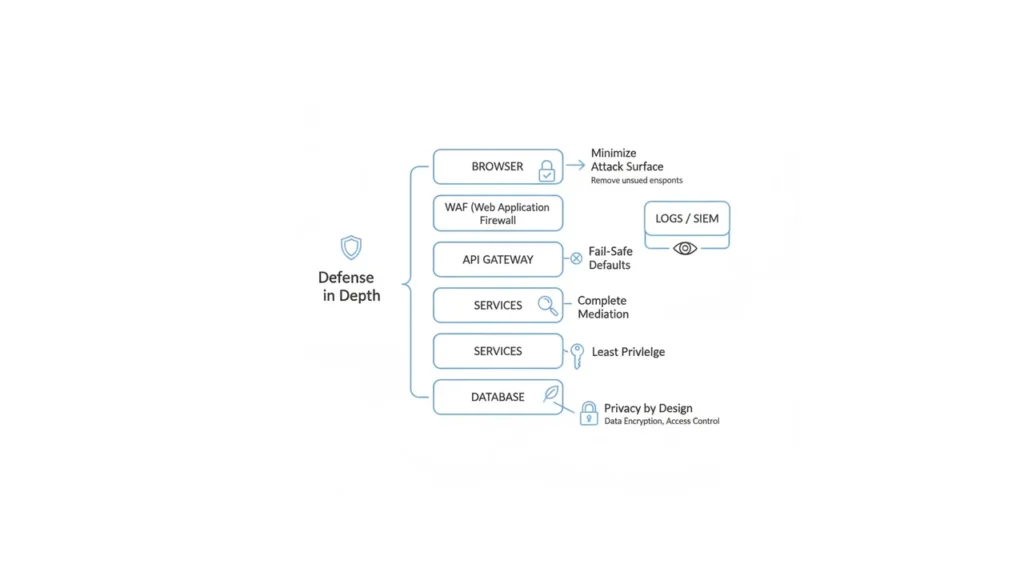

2) Defense in Depth (Layering)

Use multiple independent controls so one failure doesn’t sink the system.

Example: WAF + input validation + parameterized queries + least-priv DB + backups.

3) Fail-Safe Defaults (Secure by Default)

Default to deny; grant access explicitly.

Example: firewall default-deny rules; private S3 buckets; feature flags off by default.

4) Economy of Mechanism (Keep It Simple)

Simpler designs are easier to analyze and less bug-prone.

Example: one well-audited auth service rather than five partial ones.

5) Complete Mediation

Check authorization every time an object is accessed, not only at login or first fetch.

Example: verify ownership on every API call (/orders/:id) instead of trusting cached state.

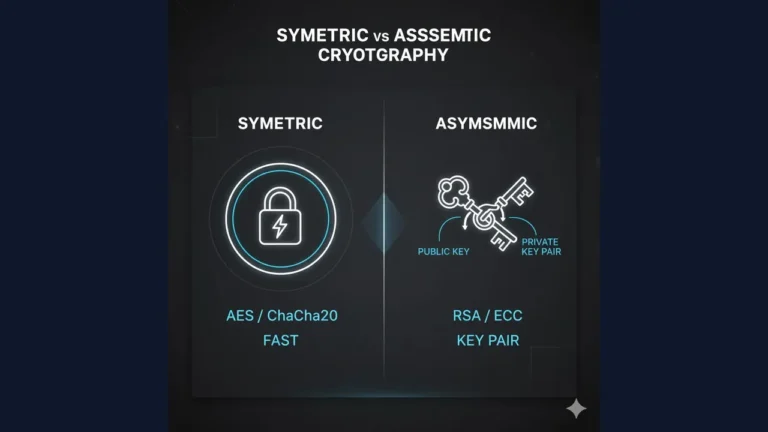

6) Open Design (Don’t Rely on Obscurity)

Security should not depend on secret designs. Algorithms and designs can be public; keys/secrets stay private.

Example: use public, peer-reviewed crypto (AES/TLS) rather than custom ciphers.

7) Separation of Privilege

Require multiple conditions for sensitive actions.

Example: two-person approval for production key rotation; MFA for payroll export.

8) Least Common Mechanism

Avoid sharing mechanisms across principals to reduce leakage paths.

Example: per-tenant storage buckets; avoid global caches for sensitive data.

9) Psychological Acceptability (Usability)

Controls must be easy to use correctly; otherwise users bypass them.

Example: password managers, SSO, clear error messages, safe defaults in UI.

10) Compartmentalization / Isolation

Design to limit blast radius when something breaks.

Example: container isolation; network segmentation; feature boundaries in microservices.

11) Secure by Design & by Default

Bake security into requirements, code reviews, pipelines, and defaults.

Example: threat modeling in backlog; SAST/DAST gates in CI; hardened base images.

12) Minimize Attack Surface

Expose fewer entry points.

Example: remove unused ports, disable test endpoints, prune third-party libraries.

13) Design for Update & Revocation

Assume change: rotate keys, patch fast, revoke tokens.

Example: versioned secrets, short-lived tokens, automated patch windows.

14) Auditability & Accountability

Create tamper-evident logs with identity, time, action, and outcome.

Example: append-only logs, centralized SIEM, clock sync (NTP), immutable storage.

15) Privacy by Design

Collect only necessary data, protect it, and respect user rights.

Example: data minimization, retention limits, anonymization/pseudonymization.

Applying Principles to a Typical Web App

Stack: SPA + API + DB on cloud; admins and users; payments.

- Least privilege:

- API service account: CRUD only for its tables.

- Read-only analytics role; separate admin role with MFA.

- Defense in depth:

- TLS everywhere, WAF, parameterized DB queries, secrets in vault, EDR on hosts.

- Fail-safe defaults:

- Private buckets; CORS allowlist; deny-all firewall; feature flags off.

- Complete mediation:

- Ownership checks on

/users/{id}and/orders/{id}each request. - Signed/expiring URLs for downloads.

- Ownership checks on

- Separation of privilege:

- Refunds require manager approval + MFA.

- CI deploys require code review + protected branches.

- Least common mechanism & isolation:

- Per-tenant schema or bucket; separate queues; namespaces per environment.

- Attack surface minimization:

- Remove

/debug, disable directory listing, trim dependencies.

- Remove

- Update & revocation:

- Key rotation every 90 days; short JWT lifetimes; revoke on password change.

- Auditability:

- Structured logs with userId/action/resource; alerts on privilege escalation.

- Privacy:

- Mask PII in logs; retention 90 days for raw events; DSAR workflow.

Anti-Patterns to Avoid

- One giant admin key used everywhere.

- Long-lived tokens (never expire).

- “Temp” debug endpoints left enabled.

- Monolithic shared DB user for all services.

- Security by obscurity (custom crypto, hidden URLs).

- Over-permissive CORS (

*) and wildcards in IAM policies. - No rollbacks/backups (violates fail-safe & resilience).

Implementation Checklist

Design & Requirements

- Threat model created (STRIDE) with top 5 risks and mitigations

- Data classification & privacy requirements defined

Identity & Access

- RBAC roles defined; least privilege enforced

- MFA for admins; break-glass account stored securely and tested

Application

- Parametrized queries; output encoding; CSRF protection

- Centralized secrets via KMS/Vault; no secrets in code

- SAST/DAST/SCA gates in CI; critical vulns block deploy

Network & Infra

- Default-deny security groups; WAF in front of public endpoints

- Separate VPC/subnets for public vs private; per-env isolation

Data & Resilience

- Backups follow 3-2-1; restore tested quarterly

- Logs centralized, immutable, with alarms for high-risk events

Operations

- Patch windows defined; key/token rotation policy set

- Incident response runbook; roles & contacts documented

The approach followed at E Lectures reflects both academic depth and easy-to-understand explanations.

People also ask:

Start with least privilege and fail-safe defaults they instantly reduce risk with minimal code changes.

No. Defense in depth layers controls; zero trust assumes no implicit trust and verifies every request. They complement each other.

Because security relies on strong keys and proven algorithms, not on secrecy of the design. Peer review improves robustness.

Maintain policies, diagrams, threat models, CI security reports, and audit logs. Map each control to a principle in a short matrix.

Collect less. Remove unneeded fields, mask PII in logs, and set data retention limits.

Adopt short-lived tokens (minutes–hours) and key rotation on a regular cadence (e.g., 60–90 days) or immediately after an incident.